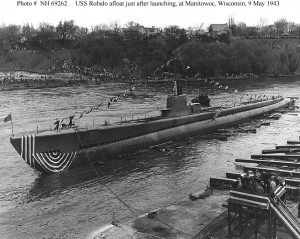

This graceful memorial is dedicated to the WWII submarine U.S.S. Robalo (SS-273). Robalo was a Gato-class submarine built in Manitowoc, Wisconsin and launched on May 9, 1943. The memorial is located in Lindenwood Park on Roger Maris Drive in Fargo, North Dakota.

This graceful memorial is dedicated to the WWII submarine U.S.S. Robalo (SS-273). Robalo was a Gato-class submarine built in Manitowoc, Wisconsin and launched on May 9, 1943. The memorial is located in Lindenwood Park on Roger Maris Drive in Fargo, North Dakota.

After the end of World War II, the U.S. Submarine Veterans of WWII assigned each of the 52 submarines lost during the war to a state. It was hoped that appropriate memorials would be constructed by each state to their assigned submarine. While most states have not constructed memorials, some have. This is one of my favorites. On the back of the memorial are the names of all the crew members lost at sea on the Robalo. The front of the memorial contains a brief history of the ship, which I quote below:

“USS Robalo SS – 273. In early January 1944, the new fleet submarine Robalo set out to join forces with the ships raging war in the Pacific. Hunting for Japanese shipping west of the Philippines, she damaged a large freighter. Her second patrol was in the South China Sea near Indo-China, where she sank a 7,500 ton tanker, the cargo of which was badly needed to fuel and drive the far flung Japanese war machine. With two battle stars to her credit, Robalo set out on her third war patrol. As she was transiting the hazardous Balabac Strait off Palawan Island on 26 July 1944, Robalo strayed into an enemy minefield. A violent explosion suddenly jolted the ship and she sank almost immediately. Four of her crewmen managed to swim to Palawan Island where they were captured by Japanese military police and imprisoned. A note dropped by one of the men in his cell window was picked up by a US soldier who was on a work detail in the same prison camp. The note recounted the events leading up to Robalo’s tragic loss. On 15 August, the four surviving Robalo crewmen were taken aboard a Japanese destroyer. The destination and ultimate fate of the destroyer are still unknown. The four survivors on board never returned. The circumstances surrounding their deaths remain a mystery, but they joined their 77 shipmates in bravely giving their lives for their country.”

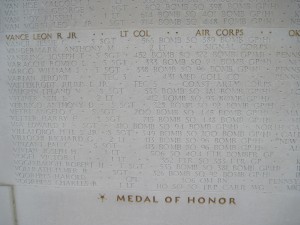

Joining the monument is a marker with the names of the North Dakota submariners and polished stone benches with the names of Commander Harold Wright, Captain Joseph Enright, and Lieutenant Commander Verne Skjonsby, all North Dakota residents who served on submarines during WWII.

This post gives me the opportunity to encourage all readers to visit one of my favorite web sites, On Eternal Patrol: http://www.oneternalpatrol.com/

Contained within this amazing web site is the history of every United States Navy submarine lost during the Second World War, listings of all the crew members lost at sea, photographs of hundreds of those lost, and links to a number of fascinating web sites detailing the history of the silent service. This is a web site not to be missed.

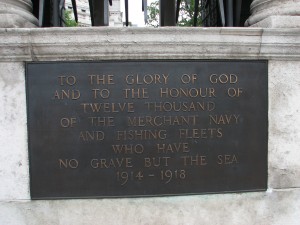

Over 32,000 U.S. Navy sailors were lost at sea from late 1941 through 1945. Over 10% of those were lost on submarines. The U.S.S. Robalo was only one of fifty-two American submarines never to return to port, one of thousands of ships from hundreds of nations on eternal patrol…