Archive for August, 2010

On opposite shorelines of St. Margarets Bay, Nova Scotia are two memorials to the victims of the September 1998 crash of Swissair Flight 111.

On opposite shorelines of St. Margarets Bay, Nova Scotia are two memorials to the victims of the September 1998 crash of Swissair Flight 111.

Swissair Flight 111 was a McDonnell Douglas MD-11 on a scheduled flight between New York’s JFK airport and Geneva, Switzerland. Faulty wiring in the first class entertainment system led to a fire. The fire found a ready fuel source in the flammable material used as insulation within the fuselage. The fire grew rapidly, resulting in instrument failure and eventual loss of control of the aircraft.

The violence of the crash is almost impossible to comprehend. The aircraft hit the water with a force of impact of at least 350 g – instantly disintegrating into 2 million pieces. The accident investigation by the Transportation Board of Canada took over four years. The human toll was 229 souls from twenty nations – lost in an instant.

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police medical examiners made every effort to identify the victims. Fingerprints, dental x-rays, and the largest DNA identification project in Canadian history eventually identified body parts from everyone on board. But there is no doubt that body parts from virtually every victim were lost at sea that fateful night, a few miles off this most beautiful part of the Nova Scotia coast.

The Canadian Government established two memorials to the dead of Swissair Flight 111 on opposite sides of St. Margarets Bay. About one-half mile from the iconic Peggy’s Cove lighthouse is a memorial made of Nova Scotia granite paying tribute to all the dead collectively. The three notches in the top corner of the monument form the number 111 – and when peered through the back side of the memorial point exactly to the crash site about seven miles offshore.

On the other side of St. Margarets Bay, near Bayswater Beach, is a larger monument listing the names of all 229 victims. Unidentified remains of the victims are also interred at this spot.

Information on the accident abounds on the Internet. Several excellent documentaries can be found on YouTube. These include actual air traffic and cockpit recordings, computer generated recreations of the events leading to the accident, and interviews with accident investigators. The memorials themselves, including enormous background material and beautiful photographs, are highlighted at the following links:

http://ns1763.ca/hfxrm/swisswhale.html (The Whalesback – Peggy’s Cove Memorial)

http://ns1763.ca/lunenco/swissbaysw.html (The Bayswater Memorial)

Aircraft accidents are perhaps the most difficult of all lost at sea scenarios for family and friends. The accidents often happen thousands of miles from where victims’ loved ones reside, whatever recovery that is possible might take weeks or months to accomplish, the accident investigation itself might take years, and the passengers themselves are generally strangers to each other – meaning that those who grieve are also strangers to each other, thrown together under the most stressful and tragic of circumstances. I suspect that beautiful memorials such as these in Nova Scotia serve to bring mourners together for a common purpose, under less stressful conditions, where time alone has performed some healing – and that strangers are strangers no more…

My last few months of U.S. Navy flight training were spent in Brunswick, Georgia. It was easy to fall in love with the Golden Isles area – as well as the entire coast of Georgia, and South & North Carolina. The beautiful beaches, salt marshes, daily afternoon thunderstorms, warm Atlantic waters, and abundance of wildlife were a constant feast for the senses for someone from the high desert of Nevada. And of course the seafood – the wonderful seafood.

My last few months of U.S. Navy flight training were spent in Brunswick, Georgia. It was easy to fall in love with the Golden Isles area – as well as the entire coast of Georgia, and South & North Carolina. The beautiful beaches, salt marshes, daily afternoon thunderstorms, warm Atlantic waters, and abundance of wildlife were a constant feast for the senses for someone from the high desert of Nevada. And of course the seafood – the wonderful seafood.

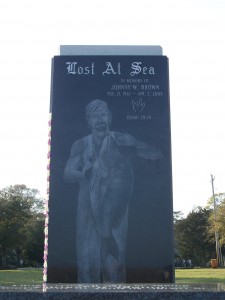

Everything has a price, however. The seafood that we all enjoy is the product of hard and dangerous work performed by brave and dedicated professionals. In the beautiful town of Murrells Inlet, South Carolina is a lost at sea memorial first envisioned as a tribute to one of those brave souls. Johnny W. Brown was a commercial fisherman sailing out of Murrells Inlet. On April 2, 2005 Johnny’s vessel was hit by a large rouge wave. His shipmates were rescued, but Johnny was lost to the Atlantic.

Johnny Brown died at the young age of 38, but there can be no doubt as to the love and respect he had to have earned in his short life. Family and friends arranged to have a memorial built to Johnny – and to others from the coastal areas of South Carolina lost at sea from whatever cause. On the first anniversary of Johnny’s loss a monument was unveiled in Morse Park Landing in Murrells Inlet. The monument consists of three black granite sides. On the side facing the jetties of Murrells Inlet is a life sized etching of Johnny. The other two sides are reserved for additional names of those lost at sea. When unveiled the monument contained 17 additional names. More have been added since – and will continue to be added, if required, annually.

This perhaps, is the purest type of lost at sea monument – a simple and beautiful memorial dedicated by family and friends to the eternal memory of loved ones gone, but most certainly not forgotten.

When I first looked at a photograph of the original 17 names added for the unveiling I was struck to see my own name on the panel. I was fascinated to read the story of the Dan Jenkins honored on the panel at the memorial web site. He was born in 1914 and lost at sea on the shrimp boat ‘Lottie C’ in October 1957. Perhaps he is a distant relative. Perhaps we simply share a name. Either way, I won’t forget where his name and memory reside.

Please visit the website for the Lost at Sea Memorial at http://www.lostatseamemorial.com/. There you can read the history of the monument, learn about all the people remembered on the panels, and obtain an application to add a name to the panels.

And please visit the fascinating YouTube video that details the construction of the monument at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5KOUwEhLdqg. The dedication of everyone is apparent and the beauty of the memorial site and surrounding area very evident. It’s a beautiful video about a beautiful memorial.

One new photograph revisiting an old post and one new memorial not previously discussed in earlier posts are today’s topics. Both of these memorials can be found near the waterfront in San Pedro, California.

One new photograph revisiting an old post and one new memorial not previously discussed in earlier posts are today’s topics. Both of these memorials can be found near the waterfront in San Pedro, California.

I previously posted a discussion of the impressive Jacob’s Ladder sculpture by Jasper D’Ambrosi. A reader of this blog has graciously provided me with a beautiful photograph of the memorial. Tamara Becker presently serves as a Second Mate and Chief Mate Unlimited on commercial ships. She also has a BA degree in Maritime History, extensive experience at sea, and a keen photographer’s eye. Of all the photographs I have seen of this memorial, Tamara’s is the best. The tenuous nature of the sailors’ hold on the ladder, the water at the lower sailor’s feet, the constant sway and twists of the Jacob’s Ladder, and the life and death tension of the entire situation is vibrantly conveyed in her superb photograph. It is my pleasure to share it with everyone. Thanks Tamara.

Another memorial in San Pedro is the Fishing Industry Memorial. Southern California became a canning location for sardines, mackerel, bluefin tuna, yellowfin tuna, and albacore in the late 1800s. Fresh fish markets became common in San Pedro south to San Diego in the early 1900s. Large fleets of purse seiners could be found in the ports of Southern California throughout the 20th Century. The Fishing Industry Memorial pays tribute to the men who lived and died bringing tuna to market. The fine photograph is courtesy of Manuel Ortiz (mortis24 on Panoramio). Thanks Manuel.

Among the most beautiful places on earth are the Canadian Maritime Provinces. Their scenic beauty is equaled by the kindness and hospitality of their citizens.

Among the most beautiful places on earth are the Canadian Maritime Provinces. Their scenic beauty is equaled by the kindness and hospitality of their citizens.

The Maritimes possess a seafarer history matched by few other locations. Elegant and timeless ships have been designed and built in the shipyards of the Maritimes – such as the “Marco Polo” from New Brunswick, the “Bluenose” from Nova Scotia, and the rum runner “Ellie J. Banks” from Prince Edward Island. The fishing industry gave life to the Maritimes. One can only hope that the lobsters remain plentiful and that the cod will someday return in great numbers.

The Maritimes have also been the location of some of the great tragedies at sea. My next few posts will discuss some of these, but I’d like to begin these posts with a thing of beauty in Peggy’s Cove, Nova Scotia.

William Edward deGarthe was born in Helsinki, Finland. He emigrated to Canada in 1926, moved to Halifax in 1945, and eventually settled permanently in the beautiful village of Peggy’s Cove in 1955. He was a painter and sculptor, his artistic work devoted to maritime subjects after his move to Peggy’s Cove. His “Fisherman’s Monument” was sculpted out of a 100 foot granite face of rock below his home. It depicts thirty-two fishermen and their wives and children enveloped in the wings of a guardian angel. The sculpture and his home (now a museum to his work) were donated to the province of Nova Scotia after his death. It is a beautiful piece of art – I’m certain meant to honor both the living and those lost at sea.

Some lost at sea memorials are touched by genius. The images they convey are timeless and universal – like all great art. The designer and sculptor of this unforgettable memorial in Wales is Brian Fell.

Some lost at sea memorials are touched by genius. The images they convey are timeless and universal – like all great art. The designer and sculptor of this unforgettable memorial in Wales is Brian Fell.

Approach the sculpture from one side or from the rear and you see a hull section of a merchant ship resting on a beach or the ocean floor, torn from the rest of the vessel, the ship’s framing exposed to the sea or the elements. Walk around to the other side and you see the face of every human lost forever to the sea incorporated in that same hull section. Expand the photos above to better appreciate this amazing piece of art.

Amethyst Marine Services Limited is the sole guardian of the memorial – a task in which they take great pride. Mr. Peter Haines of Amethyst Marine has been most generous of his time in providing me with some of the history of the sculpture and the mosaic of Italian marble on which it rests.

The memorial was commissioned in 1994 by the Cardiff Bay Arts Trust (CBAT), a charitable organization that was first established in 1991, as part of a public art effort in the Bay. Mr. Wiard Sterk of CBAT was instrumental in establishing a commission for an art piece honoring those who died in merchant service from the Cardiff Bay area. A design contest was held and the commission was awarded to Brian Fell, whose father was a merchant seaman, and who told Brian stories about ship construction methods during World War II. Once awarded the commission, Brian found the last hydraulic riveting workshop in Britain and taught himself the skills necessary to seam steel sections together to form the ship’s hull with its two very distinctive aspects. Brian’s wife served as the model for the face. The hull rests on a circular mosaic by artists Louise Shenstone and Adrian Butler. Inscribed around the edge of the mosaic are the words:

“IN MEMORY OF THE MERCHANT SEAFARERS FROM THE PORTS OF BARRY PENARTH CARDIFF WHO DIED IN TIMES OF WAR”

Peter Haines advised me that the memorial would not have happened without the efforts of the late Mr. Bill Henke MBE (Member of the Order of the British Empire). Mr. Henke was the founder of the Merchant Navy Association (Wales). He spent years raising funds for the construction of the memorial. A plaque recognizing his efforts is located just outside the circular mosaic base of the memorial – and the sculpture itself is located just outside the Welsh Senedd (parliament) building, which was built after the sculpture was erected.

The memorial is the subject of hundreds of fine photographs on Internet photo streams. Avail yourself of a look on Flickr, Flickriver, Paroramio and others. The memorial takes on different personalities under different lighting conditions, filters, and exposure levels.

I’ve spent several months researching the memorial for this short post. Two thoughts seem to run through my mind constantly about the memorial. The first is the elegant creativity of Brian Fell’s design. Few memorials possess the emotional impact of this brilliantly formed piece of riveted galvanized steel.

The second thought derives from a single line in an email from Peter Haines. When discussing Bill Henke’s essential contributions to the memorial, Peter added one final fact, which I’ll quote: “Mr. Henke actually died right next to the statue he had spent years fighting to build.”

I believe that Mr. Henke was in his early 80s at the time of his death – most of his last six decades spent serving as an active merchant seafarer, or in preserving the memories of those he knew and those he never met, but who also served at sea. I suspect late in life he took great comfort in gazing at the steel frames and riveted plates that magically form the peaceful image of friends long gone, but not forgotten. I also suspect he died at the exact place he would have wanted to be when his fellow shipmates called him to his final voyage…