USS Hobson Memorial (David O. Whitten, Ph.D.)

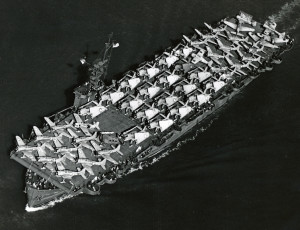

“DD 464, the USS Hobson, built in Charleston, was a veteran tin can (destroyer) with action stars aplenty. She survived World War II but sank in friendly waters after colliding with aircraft carrier USS Wasp. Hobson was steaming in formation 700 miles west of the Azres on the night of April 26, 1952. When the ships turned into the wind to allow Wasp to recover aircraft, Hobson crossed the carrier’s bow from starboard to port and was struck amidships. The force of the collision rolled the ship over, breaking her in two. The cost in lives was 176 officers and men. Loss of Hobson meant more than the deaths of sailors and the sinking of a ship. Dozens of children were orphaned and women widowed, some of the wives had suffered years of war only to lose their husbands in a peacetime accident.

The Hobson and her crew will not be forgotten so long as the pink marble memorial stands tall at the corner of White Point Gardens across the street from the Fort Sumter Hotel on Charleston’s beautiful battery. The hotel was converted into a retirement home long ago. The marble, weathered and no longer the dainty shade of pink she displayed at unveiling, bears silent witness to the loss.

My family had moved from Mt. Pleasant, South Carolina into Charleston during the summer of 1958. Because I often drove along the battery coming and going from our house on South Battery, I always studied the lovely Hobson memorial. I had read the sad story in the paper and knew that survivors and other caring citizens including sailors of the Wasp had donated the money for the monument, had it commissioned, negotiated with the City of Charleston for the spot for construction. I considered attending the memorial in Apriln but when the appointed Saturday arrived weather was windy and wet. I concluded that dedication would be postponed for better conditions and gave it no more thought until my mother announced that Chief Rhupe was on the telephone.

Rhupe was the US Navy corpsman (paramedic) assigned to the 53rd Infantry Company USMCR. It was Rhupe who did the paperwork when I enlisted in January 1957 and it was Rhupe who helped me engineer my switch to active duty for Parris Island boot camp during the summer of 1957 and back to reserve status at the end of the summer so that I could complete high school. Rhupe was the one member of the I&I staff of Marines held in high regard by everyone, reservists and other active Marines assigned to the company. If something had to be done, Rhupe did it. If Rhupe said it, nobody argued. He was the anchor of the company. A chief petty officer Rhupe was resplendent in his Marine Corps uniforms replete with his chief petty officer’s insignia and service stripes on a single sleeve. He was a handsome man with an athletic build and perfect teeth to show off a terrific smile. In Marine Corps dress blues he outshone any other Marine in view.

So what did Rhupe want with me this rainy Saturday morning? “Whitten!” he said before I could utter a word. He heard me pick up the receiver. “Yes sir?”

“Climb into your green uniform and meet me at the Hobson memorial in twenty minutes, I need you to round out a color guard! No time to discuss it, get moving!”

“But Chief,” I blurted, “why are you calling me?”

“We had everything set,” he said in exasperated tones unusual for him, “when one of the men collapsed during rehearsal out here at the training center. His appendix ruptured and we had to rush him to the hospital and that leaves me a man short for the twenty-one gun salute. I called you because I know I can count on you to show and you are smart enough to learn your part without a rehearsal.”

“What about a rifle?” I foolishly asked.

“Whitten! Do you think I haven’t taken care of that? I have the rifle and cartridge belt and I’m sitting here adjusting the belt to fit you. Tell me you’ll be there and I can get onto something else.”

“You wouldn’t call me if there were another option?” “You know I wouldn’t!”

-1-

“What about the rain Chief?”

“We go on at ten rain or shine.” He hesitated. “The rain will stop for this!”

“I’ll see you in twenty minutes.”

“Good!”

We rang off and I hurriedly told my mother what I was about and she helped me get into the

heavy wool green uniform. I drove the several blocks to the Fort Sumter Hotel, parked along South Battery and walked through to the monument site. Rhupe and the Marines were climbing out of cars parked along the side street. He grabbed me from behind because I had not seen him. Before I could say anything he slung a cartridge belt around my middle and clasped it. Of course he had sized it perfectly. I had an M1 in my grasp in another second along with a copy of the program. I looked over the list of events, folded the paper and slipped it into the inside pocket in my uniform blouse.

“There are three blank rounds and an empty clip in the first right pocket of the cartridge belt. When you get the order to lock and load put them into the rifle.” He then explained in detail what I was to do where I was to march, how I was to fire, and so on. “You did an honor guard last year, didn’t you?”

I nodded.

“I thought so! This is pretty much the same deal.” He showed one of his great smiles. “It is two minutes to ten and the rain has stopped!”

“I knew it would Chief, after all, you said it would!”

He slapped me on the back and shoved me into my place in the formation, uttered a command and we marched across the street, along the sidewalk to the monument and off to the side so that our backs were to the Ashley River.

The Gardens hosted about a hundred men, women, and children. Some of the women held infants. Everyone was sad eyed and many were weeping. Rhupe was in charge. I learned later that he had put together the honor guard with volunteers. No one was there under orders and no one was getting paid for this performance. I was the only member of the reserve company, the other Marines were from the Charleston Naval Shipyard guard mount.

Several men spoke to the group. No one held the platform for more than a few minutes. The theme was constant: the Hobson had been a magnificent ship with splendid crew. The nation and the Navy mourned their loss..

The weather was threatening and the speakers knew that this crowd, children and all, would stay any downpour to honor their lost family members, so they kept everything moving rapidly.

After about fifteen minutes of speeches during which the honor guard stood at attention, we were called to port arms and ordered to lock and load. I slipped the empty clip into the rifle and fit in two of the blank rounds. The third round I slipped into the chamber.

“Twenty-one gun” (preliminary command), “salute!”

We pulled rifles into our shoulders.

“Unlock!” I took off the safety as did the other six Marines. “Fire!”

We discharged the weapons in a cloud of smoke and noise.

“Reload!”

We pulled rifles out of our shoulders and returned them to the port position and pulled the

receiver home to remove the discharged round and put a fresh one into the chamber. Without an adaptor for blanks the M1 will not fire semiautomatically, we had to reload manually. I have never seen a twenty-one gun salute fired with M1s with adaptors, perhaps because the manual of arms used was unchanged from the one written for the bolt-action 1913 Springfield rifle.

“Aim!”

Rifles back into firing position.

“Fire!”

And a repeat produced the required twenty-one rounds.

-2-

We returned to attention while the field music (bugler) played taps. There was still no rain but there were no dry eyes.

We were dismissed and the show was over, but was it?

The crowd converged on the participants in the dedication. We were hugged and thanked by everyone. One of the women hugged me in tandem with the child she was holding. Rhupe ordered us to release the empty rounds from our rifles and as we did so the empty clips jumped out with their characteristic zing. The people around us were picking up the empty shell casings and clips and sharing them around, mementoes of the dedication. Everyone was appreciative of our willingness to perform this small favor for the survivors of Hobson.

About two minutes after we finished the rain started to fall again and the crowd made for their cars. Rhupe took the cartridge belt from me and I handed him the rifle.

“Thank you Whitten!”

I smiled and turned for the run to the car.

“Oh, Whitten?”

I turned back. “Savor this moment! There is never going to be another time when you will fire

a Marine Corps rifle without having to clean it afterwards!” I am sure that Rhupe cleaned that weapon himself.

We both laughed. He began directing his men into cars and I ran toward mine. Just in front of my mother’s 1955 Plymouth was a large white car. A man and woman with grey hair were trying to get two young children into the back seat with the help of a younger woman. I heard the man say as I hurried by, “Yes there was a printed program but I couldn’t get a copy, I asked everyone I saw but there were none to be had.

I stopped. “Excuse me. You want a copy of the dedication program?” The three adults turned to look at me and the children stopped struggling so they could see what was happening.”

The older woman spoke. “Yes, we would very much like to have a copy. Our son . . . her husband . . . their father . . .” She couldn’t finish the sentence.

I unbuttoned the top two buttons on my blouse and withdrew my copy of the paper they wanted. I handed it to the woman who had tried to speak. She took it with the reverence that would be accorded a crown jewel. “Thank you so much!”

The young woman spoke. “You don’t want it?”

“Certainly I want it!” I responded, “but it belongs to you.”

The man grabbed my hand and gave it a shake but said nothing. The older woman just cried

and the little boy, perhaps five years old, still standing in the door frame of the car, leaned out and shouted in his shrill voice as I moved away, “Thanks, Sarge!”

That was a grand salute for a private first class who would not be sarge for another three years.

The Hobson will always be a part of me. I will never forget that wet Saturday morning in Charleston when I joined the families left behind when the US Navy lost one of its own.

-3-