Archive for September, 2010

An incredible amount of information is available on the loss of the Titanic in 1912. Thus it is not necessary to discuss the accident in this blog. Interest in the shipwreck itself, however, has increased of late due to a new photographic survey conducted this summer, focusing on parts of the ship’s remains not previously observed or photographed.

An incredible amount of information is available on the loss of the Titanic in 1912. Thus it is not necessary to discuss the accident in this blog. Interest in the shipwreck itself, however, has increased of late due to a new photographic survey conducted this summer, focusing on parts of the ship’s remains not previously observed or photographed.

Memorials to the victims can be found in a variety of locations around the world – including the United States, Canada, Ireland, the United Kingdom, and Australia. Many of these memorials will be covered in future posts. Today’s post will highlight a memorial that is probably not seen by many tourists in Washington, D.C. due to its location well outside the city center.

The Washington Titanic Memorial was unveiled in May 1931 by the widow of President Taft. It was designed by Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney and sculpted by John Horrigan from a single piece of Rhode Island red granite. The original placement of the memorial was in Rock Creek Park along the Potomac River. In 1966 the memorial was removed to accommodate The Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. In 1968 it was re-erected without any ceremony on the waterfront outside Ft. McNair.

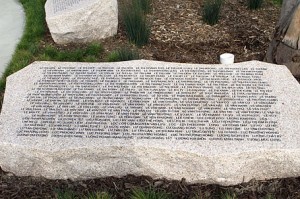

An inscription can be found on the front and back of the memorial base. It reads:

If you research the history of Ireland you will read much about the Great Famine of 1845-1852. The potato blight resulted in the deaths of an estimated one million people on the island itself. Another one million people left their homeland to relocate to America, Canada, Australia and other places of refuge around the globe. Many of those fleeing an existence of starvation sailed on what would become known forever in Ireland as Coffin Ships. They were accurately named by history. The mortality rate on these ships was often 30% or more. Tens of thousands of Irish rest on the bottom of the world’s oceans, their lives extinguished by ruthless shipowners and unscrupulous shipmasters.

‘Coffin Ships’ as a nautical term is not used strictly in association with the Irish Famine. In the lore of the sea it describes any vessel that has been overinsured, basically making it worth more to its owners at the bottom of the sea than afloat. But coffin ships became a routine hell for the Irish leaving their island during what the Irish call “The Great Hunger”. Lack of food and water, disease, and unsafe vessels led to countless journeys of misery and death. Many accounts routinely mention sharks following the ships, because so many bodies were thrown overboard during these voyages.

The Irish Government commissioned a monument to the lost souls of these voyages to mark the 150th anniversary of the Irish Famine. The haunting sculpture, by artist John Behan, depicts a coffin ship with rigging of human skeletons and bones. It is Ireland’s largest bronze sculpture and was unveiled in 1997 by Mary Robinson, the then President of Ireland. Mr. Behan’s piece, especially when viewed up close, is a work of incredible power and complexity. It is unforgettable.

I’m including two interesting links to help you appreciate the sculpture and the story of the Coffin Ships. The first link will take you to a FLICKR photo stream by Dave Bushe. Scroll through his dozen or so beautifully detailed photos of the sculpture. The other link is to a fascinating YouTube video detailing the memorial and excerpts from a diary of a voyage to Canada during the famine years.

http://www.flickr.com/photos/davebushe/50973869/in/photostream/

http://il.youtube.com/watch?v=TZIjZkiYGhI&feature=related

Translate the word into any language and it will still convey the same sobering image of a person on a long journey, fraught with hardship and danger, a long trek towards an uncertain future. Refugees have fled war, persecution, and natural disasters via the oceans for as long as boats have challenged the seven seas.

During 1975, as a U.S. Naval Officer stationed in the South China Sea, I witnessed a small part of the human drama of the Vietnamese Boat People. It was not an easy thing to see – an impossible thing to forget. With the fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975, hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese crowded into every type of boat imaginable and fled their homeland. This exodus continued for years. They sailed towards Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines, Hong Kong, and Indonesia. They sailed on overloaded vessels, many boats totally ill-equiped for the open ocean. Most refugees were rescued – initially moved to relocation camps in Asia, and eventually resettled permanently in strange countries of the Western World – the United States, Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Israel, and others. For thousands of Vietnamese refugees, however, their journeys ended in death – their bodies scattered on the ocean floor of the vast expanse of the South Pacific.

Cam Ai Tran and Hap Tu Thai and their two children escaped Vietnam by boat in 1979. Thirteen others on the same boat died and were buried at sea. Tran and Thai are now the publishers of the “Saigon Times”, based in Rosemead, California. For ten years they worked tirelessly to build a memorial to the Boat People, including the tens of thousands who died at sea. In the Spring of 2009 the Vietnamese Boat People Monument was dedicated in Westminster Memorial Park’s Asian Garden of Peaceful Eternity.

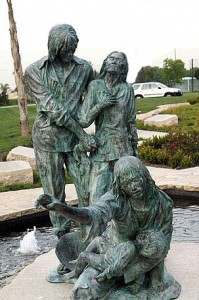

The main focus of the monument contains four statues on a slab within a pool, the slab resembling a raft. The figures on the raft are of a man, an older woman, and a younger woman holding a young child. The design is by Vietnamese artist Vi Vi. Surrounding the memorial are 54 blocks of stone, on which are engraved the names of over 6,000 deceased boat people, of which many thousands were lost at sea.

Please use the link below to visit the “Saigon Times” English translation. On the far left of their home page you will find links to many compelling stories of the Vietnamese Boat People. Start your visit by scrolling to the very bottom link on the left side. This link will take you to a page with many fine photographs detailing the design and construction of this beautiful memorial. The memorial’s total area is quite extensive, with the overall design shaped like a ship’s hull.

Like all good memorials, the Vietnamese Boat People Monument tells a compelling story. This is a story with many chapters – chapters detailing suffering and fear and sometimes death – but chapters that just as often end in survival against all odds, and in redemption…

http://translate.google.com/translate?hl=en&sl=vi&tl=en&u=http%3A%2F%2Fsaigontimesusa.com%2F