Archive for the 'Peacetime Naval Accidents' Category

In the Victoria Embankment Gardens along the river Thames in London is a memorial to the Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Navy. The memorial is a striking bronze figure of Daedalus, the ingenious craftsman of Greek legend who created wings to escape King Minos of Crete, only to lose his son Icarus when he flew too close to the sun and his wings melted. Icarus plunged into the sea…

In the Victoria Embankment Gardens along the river Thames in London is a memorial to the Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Navy. The memorial is a striking bronze figure of Daedalus, the ingenious craftsman of Greek legend who created wings to escape King Minos of Crete, only to lose his son Icarus when he flew too close to the sun and his wings melted. Icarus plunged into the sea…

The memorial was designed by Royal Academy artist and sculptor James Butler as a tribute to the more than 6,000 individuals who have given their lives in Royal Navy Air Service since World War I – 1,925 of whom have no graves except the oceans of the world.

Butler’s own words best describe the power of the statue: “I wanted Daedalus to appear mighty, strong and capable, a man and yet half machine, with wings which are an integral part of him and yet still clearly man-made and fastened crudely to his arms. He must have an air of tragedy in his countenance, after all he is mourning the death of his colleagues. With his arms outspread in this position and his head slightly bowed, there are suggestions of crucifixion which signal the sacrifice of the brave men and women in their Naval Service over the years.”

When I saw the statue a few weeks ago on a visit to London with my wife, I noticed some very small, individual tributes left at the base. One was a small wooden cross in memory of “Lt. Commander ‘Barry’ Knowles, RN”. I did some research on Commander Knowles on my return to the United States. David Barry Knowles and his crew mate Ian E. Shaw were lost in the crash of a Sea Vixen aircraft in the Irish Sea on December 4, 1967. The Sea Vixen was a beautiful but exceptionally unforgiving aircraft operated by the Royal Navy off their aircraft carriers for over a decade. Almost 60 Royal Navy aviators lost their lives flying the Sea Vixen.

The Fleet Air Arm Memorial is a truly moving and powerful symbol of the sacrifices of David Barry Knowles, Ian Shaw, and the thousands of others who gave so very much in the service of their country…

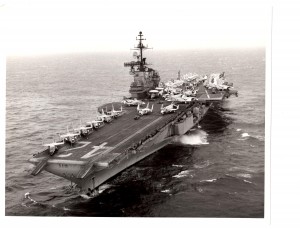

Today’s post was submitted by an old friend, Robert Schnell of Redding, California. Bob was a Radar Intercept Officer in the early 1970s, flying F-4 Phantoms with U.S. Navy Fighter Squadron 84 assigned to the aircraft carrier Franklin D. Roosevelt (CVA-42). I’ll let Bob tell the rest of his story…

Today’s post was submitted by an old friend, Robert Schnell of Redding, California. Bob was a Radar Intercept Officer in the early 1970s, flying F-4 Phantoms with U.S. Navy Fighter Squadron 84 assigned to the aircraft carrier Franklin D. Roosevelt (CVA-42). I’ll let Bob tell the rest of his story…

“The flight deck of a U.S. Navy aircraft carrier has been described as the most dangerous square footage you may trod. During flight operations ear-splitting jet engine noise, aircraft in motion, searing exhaust, jet engine intake forces so powerful it can suck a 200 pound man off the deck in a split second, spinning propellers and flight deck personnel moving among all this machinery on a confined area of about an acre in size demand a careful, deliberate choreography. It takes professional skill, knowledge and no small ability for all this activity to occur so as to get the primary mission accomplished: launching aircraft off the ship and into the air safely and efficiently. Recovery of those same aircraft during the landing sequence has its own set of rules. Even when all is done properly, as safely as possible and as efficiently as only time, training and practice may allow there still is the unknown, unforeseen circumstance that causes tragedy. Such was the case on board the USS Franklin Roosevelt aircraft carrier (FDR), CVA-42, in 1972 during a Sixth Fleet cruise in the Mediterranean Sea.

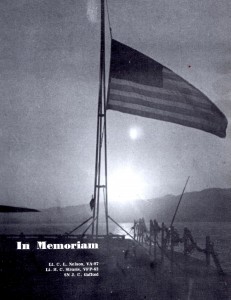

VFP-63 was a photo reconnaissance squadron flying RF-8’s which were unarmed Crusaders re-equipped with photo gear. The F-8 was equipped with an ejection seat that only promised a safe ejection if the plane was flying at least 200 feet above the surface and at a speed of at least 200 knots. It needed that much speed and altitude for the seat to function properly. The F-4’s ejection seat, by contrast, had a later model “0-0” seat; i.e., one could eject from the Phantom on the ground with no altitude or airspeed necessary. During an otherwise normal launch of an RF-8, one of those unforeseen acts happened. The plane was accelerating down the deck being pulled by the catapult. Then a portion of the underside where the catapult bridle attaches to the plane broke away. The plane was going about 100 knots and was about half the distance to the bow of the ship: moving too fast to brake and too slowly to get airborne. Without a more up-to-date ejection seat there was no way for the pilot to survive an attempted ejection. So he rode the plane until it fell over the bow into the water and was run over by the carrier. There was no hope of recovery. Lt. M.C. Steams was lost at sea.

The other accident involved an A-7 Corsair II from Attack Squadron 87 (VA-87). It also happened during a catapult launch sequence. In the Mediterranean during the summer the air is hot and humid. When a jet goes to 100% power for the catapult launch it also starts to pressurize the cockpit. Through a here-to-fore unknown set of climate-control switch positions the compression of the air inside the cockpit caused the humid ambient air to lower to the dew point where it turned instantaneously into fog. This blinded the pilot and he flew off the deck right-wing down and into the water. If he had any time to blow the canopy will never be known. It all happened in less than 5 seconds. Again, there was no hope of recovery. Lt. C.L. Nelson was also lost at sea.

Those involved in Naval Aviation who lose their lives in the performance of their duties, whether in peace or war, will always be remembered. In these two cases their coffins are the planes they flew, their tombstones are the waves of the Sea above and their memorials are the people who will never forget their ultimate sacrifice.”

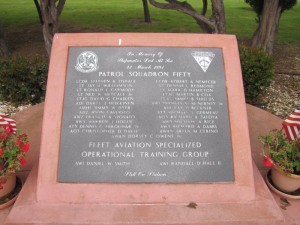

In the language of the United States Navy VP-50 was “Fixed Wing Patrol Squadron 50” – also known as the Blue Dragons. From 1946 until June 30, 1992 they were an active squadron of the United States Navy. I once flew for the U.S. Navy. The death of any aviator or any sailor has an impact on all of us who earned Navy Wings of Gold – or any of the other hard-earned insignias of naval service (surface warfare, submarines, SEALS, and the other specialties).

On March 21, 1991 two P-3C Orions of VP-50 collided about 60 miles southwest of San Diego, CA in bad weather. One aircraft was relieving the other on a normal anti-submarine patrol watch. The aircraft were stationed at Naval Air Station Moffett Field, south of San Francisco, CA. I distinctly remember reading the first newspaper reports the day after the accident – 27 U.S. Navy personnel missing at sea. That is a horrific toll for any Navy squadron, whose total personnel would only be a few hundred officers and enlisted men – especially when it happened in a single instant, in peacetime. I could only imagine the shock and sorrow within the VP-50 family and NAS Moffett Field community that day.

The cause of the accident was never determined beyond it being a mid-air collision. Pilot error was probably a contributing cause – and weather, crew fatigue, and perhaps a mechanical problem additional factors. The human cost, however, was almost instantly quantified – 27 young souls lost at sea – lost forever to their wives, children, parents, friends, and shipmates. Lost, but not forgotten.

Moffett Field Naval Air Station has been closed, but Moffett Field as a civilian airport remains. Located on its grounds is a plaque listing the names of all 27 men who perished in the Pacific Ocean that night. There is another monument to these same men in Arlington National Cemetery.

I have included three photographs in this post. One is of the monument at Moffett Field, listing the names of those who perished that night. Another is of four VP-50 aircraft in flight. And one is of two P-3C Orion aircraft flying over the Golden Gate Bridge. These are not VP-50 aircraft, but I know every man who ever flew with VP-50 out of Moffett Field witnessed this view. They loved flying for moments like this.

Please visit the VP-50 web page devoted to the men who died that night at: http://www.vpnavy.com/vp50mem_04dec98.html

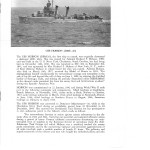

On the night of June 3, 1969 the U.S.S. Frank E. Evans (DD-754) was involved in a collision with the Royal Australian Navy aircraft carrier Melbourne in the South China Sea – an accident eerily similar to the U.S.S Hobson/U.S.S Wasp collision 17 years before. Flight operations were in progress on the Melbourne and the Evans was maneuvering into its correct position reference to the carrier. As in the Hobson incident, an error in judgement was made on the bridge of the Evans. The Melbourne struck Evans amidships, cutting her in half. The bow section of the Evans sank almost immediately, taking 74 of her crew to their deaths. One body was recovered, 73 were lost at sea. The photos at the top left show the Evans before and after the accident.

On the night of June 3, 1969 the U.S.S. Frank E. Evans (DD-754) was involved in a collision with the Royal Australian Navy aircraft carrier Melbourne in the South China Sea – an accident eerily similar to the U.S.S Hobson/U.S.S Wasp collision 17 years before. Flight operations were in progress on the Melbourne and the Evans was maneuvering into its correct position reference to the carrier. As in the Hobson incident, an error in judgement was made on the bridge of the Evans. The Melbourne struck Evans amidships, cutting her in half. The bow section of the Evans sank almost immediately, taking 74 of her crew to their deaths. One body was recovered, 73 were lost at sea. The photos at the top left show the Evans before and after the accident.

The whole story of the Evans can be found at the superb website of the U.S.S. Frank E. Evans (DD-754) Association: http://ussfrankeevansassociationdd754.org

Spend some serious time on this website. It is the finest website devoted to a single ship that I have ever seen, lovingly maintained by former members of the Evans crew during her long and proud history. She served in three wars with distinction. Her entire history is contained within the website. There are several memorials to the Evans’ lost souls in the United States, including one in Arlington National Cemetery. There is also a beautiful memorial in Australia.

There is one memorial to the Evans in the United States that personalizes the tragedy beyond all the others, however. It is not large in size. I doubt if it was designed by a professional artist or cost as much as the other Evans memorials. It is not on the beaten track either – it’s located on a plaza in a very small town called Niobrara, Nebraska.

Among the dead and forever lost at sea on that awful night in 1969 were three brother from Niobrara – Gary, Kelly and Gregory Sage. It was the worst single family toll in the U.S. Navy since the five Sullivan brothers were killed in the sinking of the U.S.S Juneau in 1942 near Guadalcanal. Even today, after four decades have passed, it’s difficult to comprehend the sense of loss that must have been felt by the brothers’ parents, the widow of one of the brothers, the immediate family, and the entire small Nebraska town that they called home.

The memorial is in two parts. One is a plaque that describes the accident. In front of and below the plaque, resting on the ground, is a simple granite block. On the front of that block are five words, one date, and a single oval photograph. The power of that photograph is how it humanizes the loss of all those souls that night. It’s hard to imagine a more powerful image on any memorial anywhere.

For more information on the Sage brothers and the 1999 dedication of this memorial, please visit the U.S.S. Frank E. Evans Association website and click their ‘News’ section. Under the same section you will find photographs of all the sailors who died that night and forever rest in the deep waters of the tropical Pacific.

For more information on the Sage brothers and the 1999 dedication of this memorial, please visit the U.S.S. Frank E. Evans Association website and click their ‘News’ section. Under the same section you will find photographs of all the sailors who died that night and forever rest in the deep waters of the tropical Pacific.

U.S.S Hobson Memorial Image © Brown Memorials

Through the kindness of Claudia Brown, President of Brown Memorials of Florence, South Carolina, I have obtained some fascinating additional information on the U.S.S Hobson Memorial in Charleston. Claudia provided me with a copy of the original program given out at the 1954 dedication of the monument. I have turned this document into scanned files to share with everyone. My apologies for the light quality of the scans. It’s a 56 year old document and is somewhat faded.

The program contains significant information on the history of the Hobson, the thought process on the design of the memorial, a dedication and listing of the 176 crew members lost in the accident, a listing of the surviving crew, and a discussion of the Memorial Society, whose hard work and dedication resulted in this permanent memorial. Claudia also provided some additional information, which I quote below:

“As a member of the American Institute of Commemorative Art, my father Bill Brown, of Brown Memorials, and Harold Schaller of Peacock Memorials in Valhalla, NY worked together on the project. It may interest you to know that this monolith made from Salisbury Pink granite quarried in Salisbury, NC, was at that time the largest piece of stone quarried from that site. It was so large that the names and carving had to be sandblasted into the stone before it was removed from the quarry.”

My sincere appreciation to Claudia Brown for providing the Dedication Program attached below. I’ll be highlighting other Brown designed memorials in future posts. Their web site can be visited at http://www.brownmemorials.com/index.html. Be sure to check out their Gallery Section, especially ‘Civic’ for other memorable Brown memorials.

And now the U.S.S. Hobson Memorial Dedication Program from 1954:

As a veteran of Naval Aviation, I have witnessed first-hand the dangers of aircraft carrier operations. While flight operations are being conducted, the activities above and below decks on a carrier must be meticulously coordinated. Mistakes all too often lead to serious accidents.

This careful coordination of activities extends beyond the aircraft carrier itself, to the support ships that escort the carrier. When viewed from an aircraft above, these support ships constantly engage in a precise ballet to remain in the proper position closely aft and to the side of the carrier to support flight launch and recovery operations. This is not an easy task. The carrier is always ‘chasing the wind’ – constantly changing heading and speed to keep sufficient wind flowing directly down the deck. The support ships are tasked with keeping proper position in relation to the carrier, often at night or in bad weather and heavy seas.

The U.S.S. Hobson (DD-464) , a Gleaves-class destroyer was built at the Charleston Navy Yard and commissioned shortly after the outbreak of WWII. During the war she saw action in North Africa, the western Atlantic, and at D-Day. Late in 1944 she was converted to a destroyer-minesweeper and reclassified DMS-26. After this conversion she saw heavy action near Okinawa, where she suffered significant casualties and damage from enemy suicide attacks. Repairs were completed after WWII and the Hobson took up duty as a destroyer-minesweeper with the Atlantic Fleet.

On the night of April 26, 1952 the Hobson was a support ship for the aircraft carrier U.S.S. Wasp (CV-18), which was conducting flight operations 700 miles west of the Azores. The Wasp began a turn into the wind to prepare for aircraft recovery. The Hobson needed to maneuver to maintain its correct position in reference to the Wasp. A tragic miscalculation took place on the Hobson bridge that night. The Hobson turned port in a maneuver that required crossing the bow of the Wasp, instead of simply falling behind the Wasp and turning in the carrier’s wake. The Hobson was struck amidships by the Wasp. The collision cut the Hobson in half. She sank in less than five minutes. 176 of her crew were lost at sea, many asleep in their berthing compartments.

I have read several accounts of the events on the bridge of the Hobson that night – the best being found in Kit Bonner’s book, Final Voyages. An official Navy inquiry laid blame on the Commanding Officer of the Hobson, Lieutenant Commander W.J. Tierney, who died in the accident. Suffice it to say that procedures broke down that night – and that 176 men paid the ultimate price for a mistake in judgement.

Governments and their military seldom build memorials to those lost in accidents – they don’t wish to draw attention to such incidents. Within the beautiful Battery area of Charleston, South Carolina, however, stands a monument to those lost in the Hobson accident. It was built and paid for by the “U.S.S. Hobson Memorial Society” – a group of former shipmates, families and friends of the lost men of the Hobson. One side of the monument briefly describes the events of April 26, 1952. The other side lists the names of the lost, and the time and date of the accident. The monument is simple as an art piece, but I find my eyes are drawn to the platform – constructed of stones collected from the 38 home states of those lost at sea in just four minutes. These stones, perhaps more than anything else about the memorial, create a visual image in color and number of the scope of the loss of life that April night. Viewed from above one can almost visualize a small ship breaking apart on a big ocean, lives from numerous states scattered on the Atlantic floor, like the stones of the platform – a boy from Ohio lies here, another from Texas lies there, and one from California there, and on and on…

Damage to the Wasp showing the violence of the collision. The Wasp lost almost 90 feet of her bow.

Jim Teresco’s fine photographs of the

U.S.S Hobson Memorial

Additional information on the history of the U.S.S. Hobson can be found at the following links:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Hobson_(DD-464)

http://www.cv18.com/hist/hobson.html