Archive for the 'Wartime Naval & Merchant Marine' Category

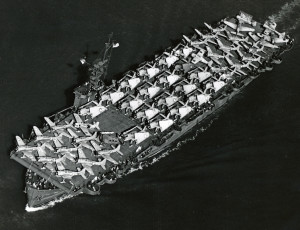

Petty Officer Doris (Dorie) Miller was the first of very many African American heroes of World War II. Miller was born and raised in Waco, Texas, joining the US Navy in 1939 at the age of 19. On December 7, 1941 Miller was stationed aboard the USS West Virginia at Pearl Harbor. Although a mess attendant collecting laundry below decks at the time of the attack, Miller hurried topside, assisting to wounded sailors (including the ship’s dying Captain), participating in damage control & rescue efforts, and finally manning a 50-caliber antiaircraft machine gun. For his courage that day Dorie Miller was awarded the Navy Cross, the Navy’s second highest award for valor, personally presented by Admiral Chester Nimitz. Miller’s story was extensively covered by the black press and civil rights organizations in the United States. The War Department sent him on a national tour to encourage enlistment. Upon completion of that tour in mid-1943 Miller was assigned to the new escort carrier Liscome Bay. The ship participated in the American offensive in the Gilbert Islands, including the bitter fighting on Tarawa. A fascinating article on Miller’s entire naval career by Michael D. Hull can be found in the February 2016 issue of “Naval History” magazine.

On November 23, 1943 the Liscome Bay was torpedoed by the Japanese submarine I-175. Violent explosions rocked the ship and she sank in twenty-three minutes. Of her 916 officers and crew, only 272 survived. Dorie Miller was lost at sea…

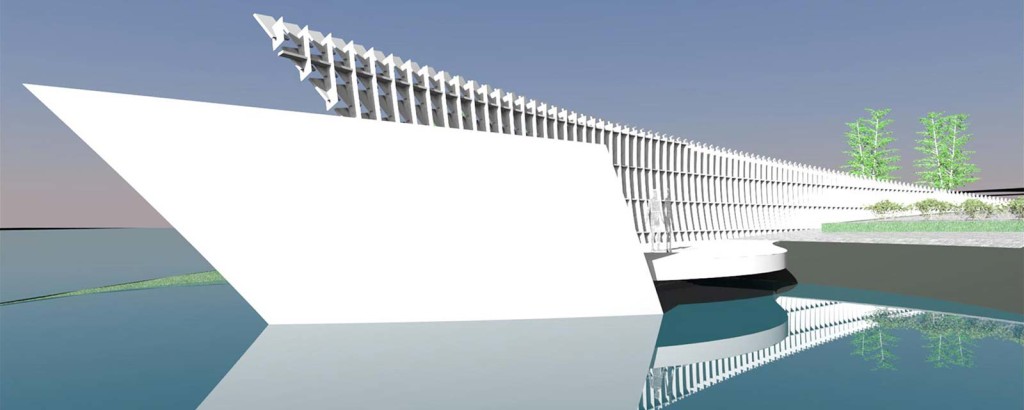

Dorie Miller has never been forgotten. Over the years Miller has been memorialized in numerous ways – schools have been named after him, a Miller Family Park was established at Pearl Harbor, a stamp bearing his likeness issued by the US Postal Service in 2010, and a US Navy Knox Class frigate the USS Miller (DE-1091) was commissioned in 1973. I have recently learned of a stunning new monument being proposed in Miller’s hometown of Waco, Texas. A rendering of the beautiful design can be seen above, and I’ll include other renderings at the end of this post. Fundraising is nearly complete. You can help complete this worthy effort by visiting the beautiful web site for this proposed memorial at http://www.dorismillermemorial.org and by making a donation. The design concept and the approved site are unforgettable. Please help make this memorial to Dorie Miller and the other lost souls on the Liscome Bay a reality.

I saw this memorial to the U.S. Navy’s Submarine Service during a recent visit to the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. I was struck by the faces in the bow wave of the submarine – perhaps lost at sea sailors watching over living shipmates on active patrols around the world.

I saw this memorial to the U.S. Navy’s Submarine Service during a recent visit to the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. I was struck by the faces in the bow wave of the submarine – perhaps lost at sea sailors watching over living shipmates on active patrols around the world.

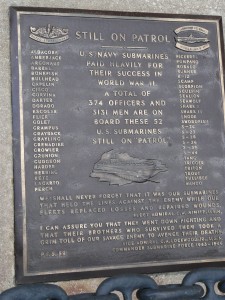

During World War II, thousands of United States Naval officers and men never returned to their home ports. Locations of some of the sunken submarines have been identified. The locations of others have never been established – and quite probably never will. The lost men are listed on various Tablets of the Missing at U.S. military cemeteries within the theater of operations where the submarines were last known to be operating. Perhaps, the spirits of all these lost men are riding the bow waves of the present submarine force – and will continue to watch their shipmates for future generations…

I recently received an email from Paul Parsons of Darnestown, Maryland suggesting two topics for this blog. Paul’s first suggestion was the bravery and sacrifice of the Asiatic Fleet in the early months of 1942. I briefly covered a small part of that history in a May 2011 post on the HMAS Sydney II and the U.S.S Houston. The Asiatic Fleet deserves much more, however. My next post will begin to rectify that oversight.

I recently received an email from Paul Parsons of Darnestown, Maryland suggesting two topics for this blog. Paul’s first suggestion was the bravery and sacrifice of the Asiatic Fleet in the early months of 1942. I briefly covered a small part of that history in a May 2011 post on the HMAS Sydney II and the U.S.S Houston. The Asiatic Fleet deserves much more, however. My next post will begin to rectify that oversight.

Paul’s other suggestion was a post about the Navy – Merchant Marine Memorial in Washington, D.C. Paul noted in his email that the memorial “..is beautiful, but in these times so comprehensive; the specifics of sacrifice are lost to most viewers. It’s location also diminishes its meaning or effect.” I agree with Paul’s observations, but with Memorial Day approaching it seems an appropriate time to focus on the memorial and some of the human sacrifice it represents. All photographs in this post are courtesy of Paul Parsons.

The Navy – Merchant Marine Memorial is located in Lady Bird Johnson Park on Columbia Island. It was designed in 1922 by Harvey Wiley Corbett and sculpted by Ernesto Begni del Piatta. It was dedicated on October 18, 1934 as a monument honoring the sailors and merchant seamen of the United States Navy and United States Merchant Marine who died at sea during WWI. Accurate statistics of American WWI deaths at sea are impossible to quantify, mainly due to the fact that the Merchant Marine had no historical office to compile their records. Best estimates are that somewhere between 2,000 and 7,200 American sailors and merchant seamen lost their lives in WWI. One observation can be made, however – none of the hundreds of people who guided and donated the funds required to construct this memorial in the 1930s envisioned the world a decade later. The number of lost souls this monument would honor would grow by a factor of ten by the end of 1945. The seven gulls riding the cresting waves witnessed sacrifice on the seven seas unknown to any previous generation.

The bloodbath of WWII would claim over 47,000 American lives in the war at sea. Thousands more would be wounded or captured. Over 250,000 Americans served in the Merchant Marine during WWII. About 1 in 25 who served were killed. It is estimated that perhaps as many as 1,700 American merchant ships were sunk during the war – victims of torpedoes, bombs, mines, kamikaze attacks, accidents, collisions, and weather at sea. The danger was constant, the sacrifices extraordinary. A statistic with particular meaning to me is that after the formal surrender of Japan in 1945 at least 87 merchant ships were severely damaged (42 sunk) in the ensuing five years, generally by striking mines. The war did not end for the merchant seaman in 1945 – danger and death most certainly continued. Please expand the photograph and read the inscription found on the memorial. I find these words to be most eloquent. On this Memorial Day I hope we all remember the past and present sacrifices of the Navy sailors, the Coast Guard sailors, and the merchant seamen who “have given life or still offer it in the performance of heroic deeds”.

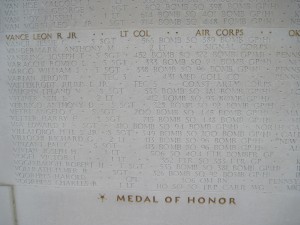

There are few more humbling experiences for an American than to visit one of the numerous American military cemeteries erected and lovingly maintained on foreign soil. I recently visited the American WWII Cemetery in Cambridge, England. Contained within its 30 acres are the graves of 3,809 Americans who lost their lives during WWII. Engraved on a 472-foot limestone wall on one side of the cemetery are the names of 5,126 others – missing in action, lost or buried at sea, or those “Unknowns” whose remains could not be positively identified prior to their interment in the cemetery.

There are few more humbling experiences for an American than to visit one of the numerous American military cemeteries erected and lovingly maintained on foreign soil. I recently visited the American WWII Cemetery in Cambridge, England. Contained within its 30 acres are the graves of 3,809 Americans who lost their lives during WWII. Engraved on a 472-foot limestone wall on one side of the cemetery are the names of 5,126 others – missing in action, lost or buried at sea, or those “Unknowns” whose remains could not be positively identified prior to their interment in the cemetery.

Time seems to stand still within the cemetery. Familiar names can be found on the Tablets of the Missing – Glenn Miller, Joseph P. Kennedy, Jr. and others. Among the graves in the cemetery are the graves of “unknowns”. Their earthly remains were never identified, yet those remains are buried in the cemetery and their names are engraved somewhere on the Tablets of the Missing. It’s an eerie feeling standing over an unknown grave and then gazing at the thousands of names on the wall – wondering which name on the wall identifies the American who gave everything resting below your feet…

I saw the grave of an American who was serving with the American Red Cross. Hugh Foster ran what was said to be the finest Red Cross canteen in all of England. Stories about his canteen can be found in many WWII memoirs. Being a non-combatant did not spare Mr. Foster from the ravages and dangers of war, however. He died in a bombing raid. He is buried among the American military men who found his canteen a welcome refuge – a place of rest and relaxation. I am certain they are honored by his presence. He is among friends.

Etched in gold lettering on the memorial wall is the name “Lt. Col Leon R. Vance, Jr.” Vance is the only serviceman honored in the cemetery to be awarded the Medal of Honor. A copy of his Medal of Honor citation is on display in the visitor’s building at the cemetery. It speaks for itself.

“For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity above and beyond the call of duty on 5 June 1944, when he led a Heavy Bombardment Group, in an attack against defended enemy coastal positions in the vicinity of Wimereaux, France. Approaching the target, his aircraft was hit repeatedly by antiaircraft fire which seriously crippled the ship, killed the pilot, and wounded several members of the crew, including Lt. Col. Vance, whose right foot was practically severed. In spite of his injury, and with 3 engines lost to the flak, he led his formation over the target, bombing it successfully. After applying a tourniquet to his leg with the aid of the radar operator, Lt. Col. Vance, realizing that the ship was approaching a stall altitude with the 1 remaining engine failing, struggled to a semi-upright position beside the copilot and took over control of the ship. Cutting the power and feathering the last engine he put the aircraft in glide sufficiently steep to maintain his airspeed. Gradually losing altitude, he at last reached the English coast, whereupon he ordered all members of the crew to bail out as he knew they would all safely make land. But he received a message over the interphone system which led him to believe 1 of the crewmembers was unable to jump due to injuries; so he made the decision to ditch the ship in the channel, thereby giving this man a chance for life. To add further to the danger of ditching the ship in his crippled condition, there was a 500-pound bomb hung up in the bomb bay. Unable to climb into the seat vacated by the copilot, since his foot, hanging on to his leg by a few tendons, had become lodged behind the copilot’s seat, he nevertheless made a successful ditching while lying on the floor using only aileron and elevators for control and the side window of the cockpit for visual reference. On coming to rest in the water the aircraft commenced to sink rapidly with Lt. Col. Vance pinned in the cockpit by the upper turret which had crashed in during the landing. As it was settling beneath the waves an explosion occurred which threw Lt. Col. Vance clear of the wreckage. After clinging to a piece of floating wreckage until he could muster enough strength to inflate his life vest he began searching for the crewmember whom he believed to be aboard. Failing to find anyone he began swimming and was found approximately 50 minutes later by an Air-Sea Rescue craft. By his extraordinary flying skill and gallant leadership, despite his grave injury, Lt. Col. Vance led his formation to a successful bombing of the assigned target and returned the crew to a point where they could bail out with safety. His gallant and valorous decision to ditch the aircraft in order to give the crewmember he believed to be aboard a chance for life exemplifies the highest traditions of the U.S. Armed Forces.”

Leon Vance survived ditching his aircraft in the English Channel, although he would lose his right foot and lower leg. After receiving medical treatment for almost two months in England he was sent back to the United States for further treatment and the possible fitting of a prosthetic foot. In one of the cruel ironies of war, the C-54 Skymaster transport on which he was flying disappeared and was presumed to have crashed in the Atlantic between Iceland and Newfoundland on July 26, 1944. No trace of the aircraft has ever been found. Leon Vance and all aboard were lost at sea…

One of the most iconic sculptures found in the United States is The Lone Sailor, a tribute to those of all the sea services. The sculpture was originally created by Stanley Bleifeld for the United States Navy Memorial in Washington, D.C. It was first erected there in 1987. There are at least eleven other other copies located around the United States.

One of the most iconic sculptures found in the United States is The Lone Sailor, a tribute to those of all the sea services. The sculpture was originally created by Stanley Bleifeld for the United States Navy Memorial in Washington, D.C. It was first erected there in 1987. There are at least eleven other other copies located around the United States.

While not a lost at sea memorial per se, it most certainly represents a scene witnessed tens of thousands of times around the world – a mariner silently waiting for his ship. In all too many cases this scene would be the mariner’s last time spent on solid ground, as he would eventually become another soul lost at sea.

The design of statue always reminds me of the opening scene in the movie “The Sand Pebbles”, as Jake Holman mutters “Hello ship” to his new vessel the San Pablo.

The beautiful photograph in this post was taken by Manuel Ortiz (Mortis24 on Panoramio). It is of the sculpture found in Long Beach, California. I love the perspective in Manuel’s photograph – the sailor looking out to sea, where an unknown fate awaits…

Maintained by the American Battle Monuments Commission, the World War II West Coast Memorial is located at the intersection of Lincoln and Harrison Boulevards in the Presidio of San Francisco. The site overlooks the area just west of the Pacific Ocean entrance to the Golden Gate Bridge, set above a quiet and winding road that hugs the coast. The memorial can be accessed by car, bicycle, or walking. Several parking places are hidden above the actual memorial.

The curved granite wall lists the names of 412 soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, and coast guardsman who met their deaths in the Pacific coastal waters of the United States, and whose remains were never recovered or identified. The inscriptions include the name, rank, service branch and State of each of these missing Americans.

Designed by Jean de Marco, the memorial won the 1965 Henry Hering award. Despite the award, it is not one of my favorite memorial designs. It seems to lack a feel for the dangers faced by those serving at sea – there isn’t any sense of drama within the design. I suspect the best time to visit might be on a stormy winter’s day, when the wind and rain and cold would give one a sense of foreboding while gazing at the Pacific. That would be an appropriate time to contemplate the 412 names engraved in gray granite, forever facing the sea where they died.