Archive for the 'Uncategorized' Category

The Atlantic Conveyor was a British container ship transporting military and humanitarian supplies to the Falkland Islands during the 1982 conflict between Great Britain and Argentina. The ship carried Wessex and Chinook helicopters, as well as Fleet Air Arm Harrier jets. On May 25, 1982 the ship was hit by several Argentine Exocet missiles. The initial attack resulted in the loss of 12 lives, including the ship’s master. The ship eventually sank on May 28, 1982, ninety miles offshore from East Falkland Island. All the ship’s deceased were lost at sea or remain within the sunken hulk of the Atlantic Conveyor.

The memorial is located on East Falkland Island. The propeller shaft points directly to the spot of the sunken remains of the ship – 90 miles offshore. The names of the 12 crewman lost at sea are engraved on the propeller hub.

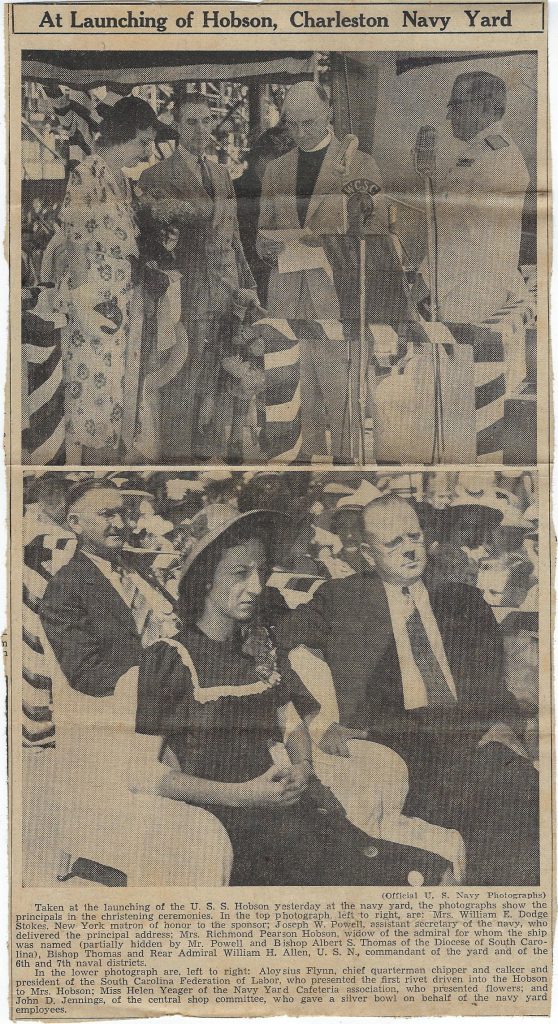

All the above images are courtesy of David O. Whitten and his wife June. Mrs. Whitten’s father, Edmond Pop, was a ship fitter in Charleston during WWII – one of the countless skilled civilians who efforts were as important to the war effort as any soldier, sailor or marine. My sincere appreciation to Mrs. Whitten and her father for this material.

Please read Mr. David Whitten’s fascinating account of serving on an honor guard at the U.S.S. Hobson Memorial in the previous post on this blog. You will not be disappointed.

USS Hobson Memorial (David O. Whitten, Ph.D.)

“DD 464, the USS Hobson, built in Charleston, was a veteran tin can (destroyer) with action stars aplenty. She survived World War II but sank in friendly waters after colliding with aircraft carrier USS Wasp. Hobson was steaming in formation 700 miles west of the Azres on the night of April 26, 1952. When the ships turned into the wind to allow Wasp to recover aircraft, Hobson crossed the carrier’s bow from starboard to port and was struck amidships. The force of the collision rolled the ship over, breaking her in two. The cost in lives was 176 officers and men. Loss of Hobson meant more than the deaths of sailors and the sinking of a ship. Dozens of children were orphaned and women widowed, some of the wives had suffered years of war only to lose their husbands in a peacetime accident.

The Hobson and her crew will not be forgotten so long as the pink marble memorial stands tall at the corner of White Point Gardens across the street from the Fort Sumter Hotel on Charleston’s beautiful battery. The hotel was converted into a retirement home long ago. The marble, weathered and no longer the dainty shade of pink she displayed at unveiling, bears silent witness to the loss.

My family had moved from Mt. Pleasant, South Carolina into Charleston during the summer of 1958. Because I often drove along the battery coming and going from our house on South Battery, I always studied the lovely Hobson memorial. I had read the sad story in the paper and knew that survivors and other caring citizens including sailors of the Wasp had donated the money for the monument, had it commissioned, negotiated with the City of Charleston for the spot for construction. I considered attending the memorial in Apriln but when the appointed Saturday arrived weather was windy and wet. I concluded that dedication would be postponed for better conditions and gave it no more thought until my mother announced that Chief Rhupe was on the telephone.

Rhupe was the US Navy corpsman (paramedic) assigned to the 53rd Infantry Company USMCR. It was Rhupe who did the paperwork when I enlisted in January 1957 and it was Rhupe who helped me engineer my switch to active duty for Parris Island boot camp during the summer of 1957 and back to reserve status at the end of the summer so that I could complete high school. Rhupe was the one member of the I&I staff of Marines held in high regard by everyone, reservists and other active Marines assigned to the company. If something had to be done, Rhupe did it. If Rhupe said it, nobody argued. He was the anchor of the company. A chief petty officer Rhupe was resplendent in his Marine Corps uniforms replete with his chief petty officer’s insignia and service stripes on a single sleeve. He was a handsome man with an athletic build and perfect teeth to show off a terrific smile. In Marine Corps dress blues he outshone any other Marine in view.

So what did Rhupe want with me this rainy Saturday morning? “Whitten!” he said before I could utter a word. He heard me pick up the receiver. “Yes sir?”

“Climb into your green uniform and meet me at the Hobson memorial in twenty minutes, I need you to round out a color guard! No time to discuss it, get moving!”

“But Chief,” I blurted, “why are you calling me?”

“We had everything set,” he said in exasperated tones unusual for him, “when one of the men collapsed during rehearsal out here at the training center. His appendix ruptured and we had to rush him to the hospital and that leaves me a man short for the twenty-one gun salute. I called you because I know I can count on you to show and you are smart enough to learn your part without a rehearsal.”

“What about a rifle?” I foolishly asked.

“Whitten! Do you think I haven’t taken care of that? I have the rifle and cartridge belt and I’m sitting here adjusting the belt to fit you. Tell me you’ll be there and I can get onto something else.”

“You wouldn’t call me if there were another option?” “You know I wouldn’t!”

-1-

“What about the rain Chief?”

“We go on at ten rain or shine.” He hesitated. “The rain will stop for this!”

“I’ll see you in twenty minutes.”

“Good!”

We rang off and I hurriedly told my mother what I was about and she helped me get into the

heavy wool green uniform. I drove the several blocks to the Fort Sumter Hotel, parked along South Battery and walked through to the monument site. Rhupe and the Marines were climbing out of cars parked along the side street. He grabbed me from behind because I had not seen him. Before I could say anything he slung a cartridge belt around my middle and clasped it. Of course he had sized it perfectly. I had an M1 in my grasp in another second along with a copy of the program. I looked over the list of events, folded the paper and slipped it into the inside pocket in my uniform blouse.

“There are three blank rounds and an empty clip in the first right pocket of the cartridge belt. When you get the order to lock and load put them into the rifle.” He then explained in detail what I was to do where I was to march, how I was to fire, and so on. “You did an honor guard last year, didn’t you?”

I nodded.

“I thought so! This is pretty much the same deal.” He showed one of his great smiles. “It is two minutes to ten and the rain has stopped!”

“I knew it would Chief, after all, you said it would!”

He slapped me on the back and shoved me into my place in the formation, uttered a command and we marched across the street, along the sidewalk to the monument and off to the side so that our backs were to the Ashley River.

The Gardens hosted about a hundred men, women, and children. Some of the women held infants. Everyone was sad eyed and many were weeping. Rhupe was in charge. I learned later that he had put together the honor guard with volunteers. No one was there under orders and no one was getting paid for this performance. I was the only member of the reserve company, the other Marines were from the Charleston Naval Shipyard guard mount.

Several men spoke to the group. No one held the platform for more than a few minutes. The theme was constant: the Hobson had been a magnificent ship with splendid crew. The nation and the Navy mourned their loss..

The weather was threatening and the speakers knew that this crowd, children and all, would stay any downpour to honor their lost family members, so they kept everything moving rapidly.

After about fifteen minutes of speeches during which the honor guard stood at attention, we were called to port arms and ordered to lock and load. I slipped the empty clip into the rifle and fit in two of the blank rounds. The third round I slipped into the chamber.

“Twenty-one gun” (preliminary command), “salute!”

We pulled rifles into our shoulders.

“Unlock!” I took off the safety as did the other six Marines. “Fire!”

We discharged the weapons in a cloud of smoke and noise.

“Reload!”

We pulled rifles out of our shoulders and returned them to the port position and pulled the

receiver home to remove the discharged round and put a fresh one into the chamber. Without an adaptor for blanks the M1 will not fire semiautomatically, we had to reload manually. I have never seen a twenty-one gun salute fired with M1s with adaptors, perhaps because the manual of arms used was unchanged from the one written for the bolt-action 1913 Springfield rifle.

“Aim!”

Rifles back into firing position.

“Fire!”

And a repeat produced the required twenty-one rounds.

-2-

We returned to attention while the field music (bugler) played taps. There was still no rain but there were no dry eyes.

We were dismissed and the show was over, but was it?

The crowd converged on the participants in the dedication. We were hugged and thanked by everyone. One of the women hugged me in tandem with the child she was holding. Rhupe ordered us to release the empty rounds from our rifles and as we did so the empty clips jumped out with their characteristic zing. The people around us were picking up the empty shell casings and clips and sharing them around, mementoes of the dedication. Everyone was appreciative of our willingness to perform this small favor for the survivors of Hobson.

About two minutes after we finished the rain started to fall again and the crowd made for their cars. Rhupe took the cartridge belt from me and I handed him the rifle.

“Thank you Whitten!”

I smiled and turned for the run to the car.

“Oh, Whitten?”

I turned back. “Savor this moment! There is never going to be another time when you will fire

a Marine Corps rifle without having to clean it afterwards!” I am sure that Rhupe cleaned that weapon himself.

We both laughed. He began directing his men into cars and I ran toward mine. Just in front of my mother’s 1955 Plymouth was a large white car. A man and woman with grey hair were trying to get two young children into the back seat with the help of a younger woman. I heard the man say as I hurried by, “Yes there was a printed program but I couldn’t get a copy, I asked everyone I saw but there were none to be had.

I stopped. “Excuse me. You want a copy of the dedication program?” The three adults turned to look at me and the children stopped struggling so they could see what was happening.”

The older woman spoke. “Yes, we would very much like to have a copy. Our son . . . her husband . . . their father . . .” She couldn’t finish the sentence.

I unbuttoned the top two buttons on my blouse and withdrew my copy of the paper they wanted. I handed it to the woman who had tried to speak. She took it with the reverence that would be accorded a crown jewel. “Thank you so much!”

The young woman spoke. “You don’t want it?”

“Certainly I want it!” I responded, “but it belongs to you.”

The man grabbed my hand and gave it a shake but said nothing. The older woman just cried

and the little boy, perhaps five years old, still standing in the door frame of the car, leaned out and shouted in his shrill voice as I moved away, “Thanks, Sarge!”

That was a grand salute for a private first class who would not be sarge for another three years.

The Hobson will always be a part of me. I will never forget that wet Saturday morning in Charleston when I joined the families left behind when the US Navy lost one of its own.

-3-

A recent communication from Mr. Phil Short of the Southport Yacht Club of Australia renewed my interest in the Pamir. I quote his comments below:

“I have discovered a Plaque well fixed to a tree dedicated to the ships company who were lost on the Pamir, on South Stradbroke Island in Queensland Australia. The area is now in the hands of the Southport Yacht Club. The previous owner’s were the Dux family, oyster farmers in the area. Looking back through Dux family history, they were from Germany.

Would like to know more about the crew, if there were any relation’s to the Dux family onboard? Angie Dux died in 1962?

The club is going to restore the area as a memorial to all lost at sea.”

Phil – I edited a few things that got lost on the internet from Australia to California. Please correct anything I got incorrect. Dan.

If anyone has any information that would be of interest to Phil, please pass it along. I will make certain that it gets to him promptly.

Please remember the Pamir!

11/11/18 Update:

Hi Dan.

Remember some time back we were discussing a Brass Plaque as a memorial of the foundering of the Pamir in 1957 at the Southport Yacht Clubs out-post on South Stradbroke Island well we have come across the person who fixed the plaque to the tree- see below.

Bruce Duncan had been a very active member of the Surfers Paradise Rotary Club and Volunteer Marine Rescue for over 30 years and was a sailor onboard the Pamir. Bruce unfortunately passed away a couple of years ago, however it has been informed to the Club that Bruce was responsible for placing the below plaque at Dux Anchorage. The plaque was placed at Dux as part of a Pamir reunion here on the coast in the mid 1980’s. Bruce was a very active member of IYFR (International Yachting Fellowship of Rotarians) and stood as a World Commodore at one stage.

Thank you to our wonderful Club members who provided the below details regarding the mysterious plaque located at Dux Anchorage. Such a wonderful and in sighting story.

Phil Short

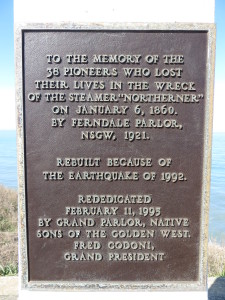

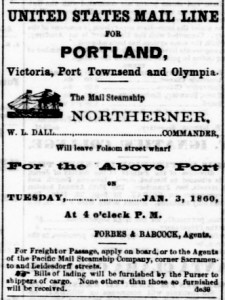

My favorite Lost at Sea memorials are the ones found off the beaten track. Centerville Beach is located north of Cape Mendocino, approximately five miles west of the village of Ferndale. The beach is nine miles long, with sweeping vistas of the Pacific to the west and the redwoods to the east. On most days you’re likely to have the entire beach to yourself. On a tall bluff overlooking the beach is a tall white cross, a monument to the steamship SS Northerner, lost on January 6, 1860.

The Northerner was built in 1847 in New York City. She spent her first few years serving the east coast of the United States, but eventually moved to San Francisco, where she established a regular passenger and mail route from San Francisco to the Columbia River and north to Washington. Her last voyage from San Francisco ended when she hit a submerged rock just a few miles offshore from Centerville Beach. The ship was carrying 108 persons at the time of the wreck. 70 people were saved, mostly due to the heroic efforts of the local citizens living around Ferndale. 38 others perished. Some bodies were eventually recovered and buried on a bluff overlooking the site of the wreck. Other victims were lost to the Pacific…

In 1921 a white cross monument was built directly above the burial site of the recovered dead. The original monument was destroyed in an earthquake centered in Cape Mendocino in 1991. Local residents rebuilt the monument and it was rededicated on February 11, 1995. It serves as a stark reminder of the dangers of ocean travel – and as a memorial to lives lost at sea in this remote and most beautiful area.

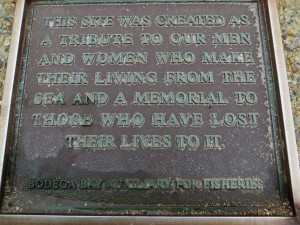

Many of the monuments on this blog are great works of art. Others are quite simple, yet powerful in their own way. This monument is located on Bodega Head, just outside the fishing community of Bodega Bay, California. It looks west over the Pacific. At one time Bodega Bay was one of the largest salmon fishing ports in the world. It is now reduced in size, yet fishing remains a vital part of the local economy. There is seldom a year where local fishermen are not not lost at sea.

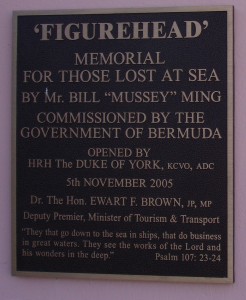

The most enjoyable and satisfying aspect of writing this blog is hearing from strangers commenting on a post or directing my attention to a memorial previously unknown to me. Recently I received an email from Nadia Ming, calling my attention to the Figurehead Memorial on St. David’s Island, Bermuda. My sincere appreciation to her for all the background information for this post. All Photographs in the post are courtesy of Nadia Ming.

The memorial was originally proposed in January 2003, when two fishermen were lost at sea in rough weather. The memorial, by Bermuda artist and native Bill Ming, was dedicated on November 5, 2005 by HRH Prince Andrew, the Duke of York.

I often speculate about the thought process of the artist when writing these posts. This post is special, however, as Nadia Ming provided me with Bill’s original vision for the project.

Maquette for Memorial for Those Lost at Sea

“As an ex-seaman who worked aboard the Queen of Bermuda I felt inspired and motivated to submit my representation of the Memorial for Those Lost at Sea. The theme of maritime life is very close to my art and ideas therefore this sculpture is intended to be a work of commemoration for the known and unknown souls lost to the tides of time yet alive through our memories and chronicles.

This memorial should honour our local fishermen/women who cast their nets and pots to scrape an existence from their catch. Bermudians lost to their loved ones as a result of storms or hurricane and the African slaves who perished during the long arduous Middle Passage.

I have tried to capture these elements, creating the spirit of a beacon that acts as a guiding and welcoming sight in times of storm and calm, a lookout for sailors who sail beyond that horizon of hope.

The form of my sculpture takes the shape of an upturned vessel, which points to the skies and stands erect on a compass due east. Barnacles, shells and a map of Bermuda tattoo the face/mask like limpets clinging to a hulks underbelly. These would stand proud of the surface providing tactile information for people with visual impairments.

Braids of rope frame a cabinet, which houses a paddle for that proverbial creek; an hourglass with sand running out and a life preserver to keep ones head above the water. Overseeing these articles shelters an open logbook that can display the names of all ”Bermudians lost at sea,” alternatively the base could also provide space for names, which would be visually accessible for people in wheelchairs.

I envisage that the final design could be produced in metal (possibly bronze) and/or stone, which would be sympathetic to the site and have durability.”

I believe Mr. Ming captured every element he envisioned in this beautiful memorial. The artist is pictured in the first picture below. I encourage everyone to learn more about Mr. Ming and his art at: http://www.billming.com/index.php

Nadia pointed out two very important additional elements of the memorial in her emails. The first was that The Figurehead Memorial is also part of The African Diaspora Heritage Trail (ADHT), which has been officially designated part of UNESCO Slave Route Project. Take the time to visit the ADHT website at: http://www.adht.bm. I think you will find yourself, like me, spending many fascinating hours learning about “the global narrative of people and culture of African descent” – and the very valuable and important effort to encourage everyone to visit these sites of historical and cultural importance and enrichment.

Information on the UNESCO Slave Route Project can be found at :http://www.unesco.org/new/en/culture/themes/dialogue/the-slave-route.

Men and women of African descent have sailed the oceans since the beginning of recorded history. The earliest known ocean voyages were from Northern Africa to Malta and Crete. During the Great Age of Sail (1600 – 1850) over 20% of all able-bodied seamen were of African descent – some were slaves, but most were free Blacks. Today they still command and crew the warships, merchant vessels, passenger ships and fishing fleets of the world – and daily face the dangers and the majesty of the open ocean.

Approximately 70 names of those lost at sea from Bermuda are engraved at the base of the memorial. All their names can be found at: http://bernews.com/2010/03/lost-at-sea-memorial-full-list-of-names/.

In closing this post, the poem below is inscribed in the open pages of the logbook on the memorial. The poet’s words were inspired by the book of Revelations of St. John the Divine, Chapter 10:5,6 – “And the angel whom I saw standing on the sea and upon the earth lifted up his hand to heaven. And swore by him that liveth for ever and ever, who created heaven and the things that are in it, and the earth and the things that are in it, that time should be no longer.”

THE END OF TIME

“Upon the restless rolling deep

That once the mighty tempest spawned;

Now lies the racing crest asleep.

Beneath that peaceful glassy plain;

All ships and men are there interred;

And all are ‘neath that blanket lain;

Tho’ strove with main now undisturbed.

Beneath that awful silent shroud;

Beneath that fearful mocking stew;

Mingled bone and steel as one

Forever wed as silten brew.

Wreckage, war and nature’s knife;

Trophies piled are theirs to be;

But wills again ‘lasting life,

Victorious, glorious, – NO MORE THE SEA”

By the late Allan E. Doughty Sr. 1922-2013

For a variety of reasons I have been unable to update this blog for several months. To get started again I thought I’d insert a post featuring the sand sculpture art of Peter Vogelaar and David Ducharme. I came across this fascinating lost at sea sculpture while researching the rescue of three New Zealand teenagers who were lost for 50 days in the Pacific in 2010 – and who amazingly survived. You can find their story at http://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/26/world/asia/26lost.html

You should also visit a YouTube video featuring the work of artist Peter Vogelaar. It can be found by clicking the following link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hhMCwU058EQ

My wife and I recently returned from a trip to Newfoundland. There is probably no place on earth where the lives and fortunes of the residents have been more closely associated with the oceans – from cod fishing on the Grand Banks, to naval service in war, to oil exploration southeast of the island. The music and literature of the province are rich in the lore and history of their love and respect of the sea – from the original discoveries of the Vikings and Captain Cook, to the history and mismanagement of the cod fishing grounds, to the economic promise and environmental dangers of the offshore oil discoveries.

Every bookstore is filled with the histories of ships and their crews, with volumes devoted to ships lost at sea, to additional volumes about remarkable rescues and stories of survival. The people of Newfoundland fully embrace this history of hardship and challenge. It defines them in the same way the Amazon defines Brazil.

This post is mainly a compilation of random photographs from around the province – from monuments to discovery, to shipwreck sites (S.S. Ethie), to a beautiful memorial outside Gander constructed to the memory of 256 individuals killed in the crash of Arrow Air Flight 1285 just outside Gander on December 12, 1985. Almost every fatality, with the exception of the aircraft crew, was a member of the 101st Airborne returning from peacekeeping duty in the Middle East. The memorial was constructed by private citizens in Gander, on the exact location of the crash. The decision of the citizens to focus of the peacekeeping efforts of the 101st Airborne results in an uplifting experience for all who take the time to visit the memorial.

I recently received an email from Paul Parsons of Darnestown, Maryland suggesting two topics for this blog. Paul’s first suggestion was the bravery and sacrifice of the Asiatic Fleet in the early months of 1942. I briefly covered a small part of that history in a May 2011 post on the HMAS Sydney II and the U.S.S Houston. The Asiatic Fleet deserves much more, however. My next post will begin to rectify that oversight.

I recently received an email from Paul Parsons of Darnestown, Maryland suggesting two topics for this blog. Paul’s first suggestion was the bravery and sacrifice of the Asiatic Fleet in the early months of 1942. I briefly covered a small part of that history in a May 2011 post on the HMAS Sydney II and the U.S.S Houston. The Asiatic Fleet deserves much more, however. My next post will begin to rectify that oversight.

Paul’s other suggestion was a post about the Navy – Merchant Marine Memorial in Washington, D.C. Paul noted in his email that the memorial “..is beautiful, but in these times so comprehensive; the specifics of sacrifice are lost to most viewers. It’s location also diminishes its meaning or effect.” I agree with Paul’s observations, but with Memorial Day approaching it seems an appropriate time to focus on the memorial and some of the human sacrifice it represents. All photographs in this post are courtesy of Paul Parsons.

The Navy – Merchant Marine Memorial is located in Lady Bird Johnson Park on Columbia Island. It was designed in 1922 by Harvey Wiley Corbett and sculpted by Ernesto Begni del Piatta. It was dedicated on October 18, 1934 as a monument honoring the sailors and merchant seamen of the United States Navy and United States Merchant Marine who died at sea during WWI. Accurate statistics of American WWI deaths at sea are impossible to quantify, mainly due to the fact that the Merchant Marine had no historical office to compile their records. Best estimates are that somewhere between 2,000 and 7,200 American sailors and merchant seamen lost their lives in WWI. One observation can be made, however – none of the hundreds of people who guided and donated the funds required to construct this memorial in the 1930s envisioned the world a decade later. The number of lost souls this monument would honor would grow by a factor of ten by the end of 1945. The seven gulls riding the cresting waves witnessed sacrifice on the seven seas unknown to any previous generation.

The bloodbath of WWII would claim over 47,000 American lives in the war at sea. Thousands more would be wounded or captured. Over 250,000 Americans served in the Merchant Marine during WWII. About 1 in 25 who served were killed. It is estimated that perhaps as many as 1,700 American merchant ships were sunk during the war – victims of torpedoes, bombs, mines, kamikaze attacks, accidents, collisions, and weather at sea. The danger was constant, the sacrifices extraordinary. A statistic with particular meaning to me is that after the formal surrender of Japan in 1945 at least 87 merchant ships were severely damaged (42 sunk) in the ensuing five years, generally by striking mines. The war did not end for the merchant seaman in 1945 – danger and death most certainly continued. Please expand the photograph and read the inscription found on the memorial. I find these words to be most eloquent. On this Memorial Day I hope we all remember the past and present sacrifices of the Navy sailors, the Coast Guard sailors, and the merchant seamen who “have given life or still offer it in the performance of heroic deeds”.