Archive for the 'Commercial Shipping' Category

It is my distinct pleasure to compose this post about the “El Faro Salute!” memorial overlooking the magnificent harbor in Rockland, Maine. My pleasure derives from my communication with the memorial’s creator and artist JBONE (the artist formally known as Jay Sawyer). All of the photographs and web site links are courtesy of JBONE, with the exception of the photograph of the ship itself. JBONE is a native of Rockland. He graduated from the Maine Maritime Academy, moving on to a career in the US Merchant Marine. He lived the life of the El Faro crew, which is evident in simply contemplating his design of the memorial – loyalty to ship and shipmates. I encourage all to visit the attached web links and videos relating to the memorial – and to JBONE’S artist web site, which add more background to this memorial and to his other fascinating art.

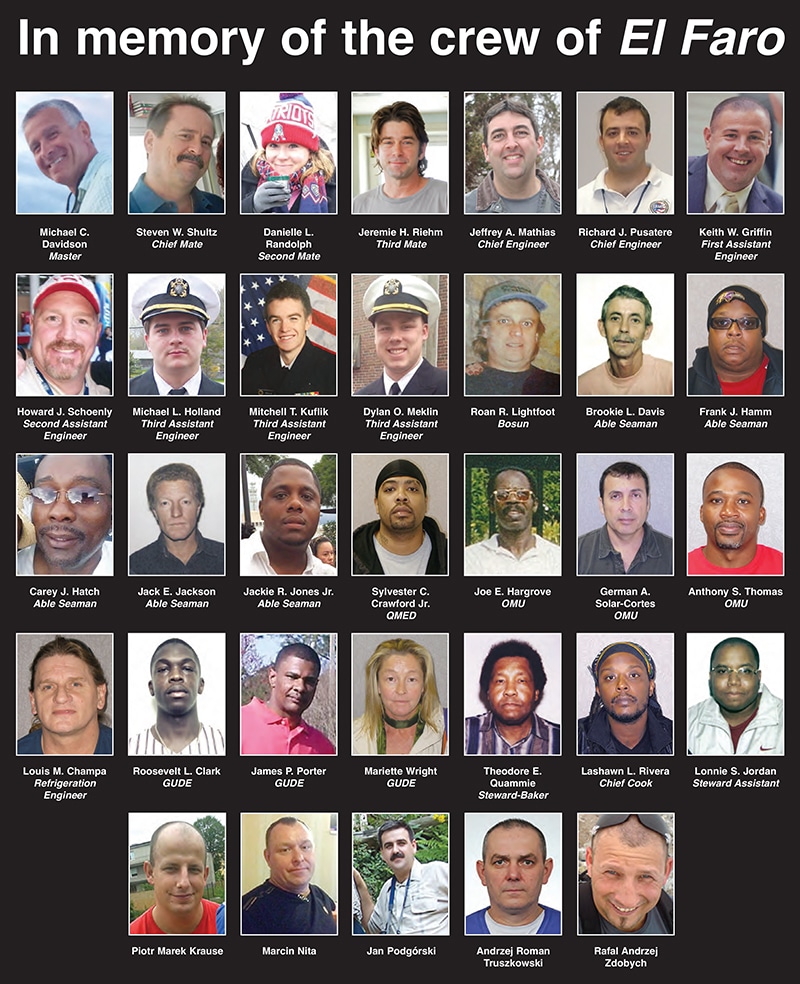

The El Faro (the “Lighthouse”) was a US flagged container ship built in 1975. She was lost at sea with her entire crew on October 1, 2015, after sailing into Hurricane Joaquin on a voyage from Jacksonville, Florida to San Juan, Puerto Rico – a routine voyage for the ship and crew. Her entire crew of 33 perished, several originally from Maine and graduates of the Maine Maritime Academy. The National Transportation Safety Board report of the accident can be found at: https://www.ntsb.gov/investigations/Pages/DCA16MM001.aspx

Jay Sawyer (the artist now known as JBONE) spent seven years designing, creating, and installing this memorial on what can only be described as an amazing location overlooking Rockland harbor and the Atlantic beyond. The male and female mariners salute you and their shipmates as they sail into their future. Below those figures the visitor can look through the stern portholes of the sculpture to the harbor and the Atlantic Ocean in the distance – the location of the final resting place of the El Faro crew.

Who better to tell the story of the memorial than the artist. Attached are two pdf documents written by the artist himself. Imbedded in two of the photographs within the first document (Glorious Day of Remembrance) are links to video interviews with JBONE. I encourage everyone to view the interviews.

Another fascinating video covering the 10th anniversary of the El Faro loss can be found at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=74g91-e0Eeg. I especially appreciated the effect of the memorial on the families of the El Faro crew.

Any lost at sea memorial is essentially about precious lives cut short. Please remember those on the El Faro now standing permanent watch on the sea they loved and sailed.

And last, but certainly not least, please visit the JBONE Studio website at https://studiojbone.com. You will learn more about the El Faro memorial and have the opportunity to view the artist’s fascinating other work.

A recent communication from Mr. Phil Short of the Southport Yacht Club of Australia renewed my interest in the Pamir. I quote his comments below:

“I have discovered a Plaque well fixed to a tree dedicated to the ships company who were lost on the Pamir, on South Stradbroke Island in Queensland Australia. The area is now in the hands of the Southport Yacht Club. The previous owner’s were the Dux family, oyster farmers in the area. Looking back through Dux family history, they were from Germany.

Would like to know more about the crew, if there were any relation’s to the Dux family onboard? Angie Dux died in 1962?

The club is going to restore the area as a memorial to all lost at sea.”

Phil – I edited a few things that got lost on the internet from Australia to California. Please correct anything I got incorrect. Dan.

If anyone has any information that would be of interest to Phil, please pass it along. I will make certain that it gets to him promptly.

Please remember the Pamir!

11/11/18 Update:

Hi Dan.

Remember some time back we were discussing a Brass Plaque as a memorial of the foundering of the Pamir in 1957 at the Southport Yacht Clubs out-post on South Stradbroke Island well we have come across the person who fixed the plaque to the tree- see below.

Bruce Duncan had been a very active member of the Surfers Paradise Rotary Club and Volunteer Marine Rescue for over 30 years and was a sailor onboard the Pamir. Bruce unfortunately passed away a couple of years ago, however it has been informed to the Club that Bruce was responsible for placing the below plaque at Dux Anchorage. The plaque was placed at Dux as part of a Pamir reunion here on the coast in the mid 1980’s. Bruce was a very active member of IYFR (International Yachting Fellowship of Rotarians) and stood as a World Commodore at one stage.

Thank you to our wonderful Club members who provided the below details regarding the mysterious plaque located at Dux Anchorage. Such a wonderful and in sighting story.

Phil Short

Old friend, former naval officer, and past contributor to this blog Bob Schnell (see March 2011 U.S.S. Roosevelt post) send me the photos for this post.

Old friend, former naval officer, and past contributor to this blog Bob Schnell (see March 2011 U.S.S. Roosevelt post) send me the photos for this post.

Trinidad Head, California is located in Northern California – north of the cities of Eureka and Arcata. The area has a long maritime history, from fishing to the shipping of redwood lumber to the large ports of the west coast. Below the Trinidad Head lighthouse is a memorial to those lost at sea from the local area. One addition to this memorial that I’ve never seen before is the addition of panels of locals who decided to be buried at sea. I think this adds a nice touch to a memorial located at one of the most beautiful spots in California.

My favorite Lost at Sea memorials are the ones found off the beaten track. Centerville Beach is located north of Cape Mendocino, approximately five miles west of the village of Ferndale. The beach is nine miles long, with sweeping vistas of the Pacific to the west and the redwoods to the east. On most days you’re likely to have the entire beach to yourself. On a tall bluff overlooking the beach is a tall white cross, a monument to the steamship SS Northerner, lost on January 6, 1860.

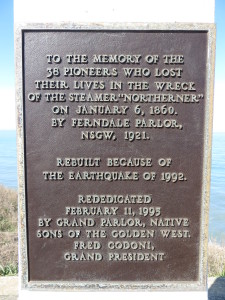

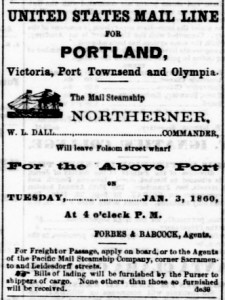

The Northerner was built in 1847 in New York City. She spent her first few years serving the east coast of the United States, but eventually moved to San Francisco, where she established a regular passenger and mail route from San Francisco to the Columbia River and north to Washington. Her last voyage from San Francisco ended when she hit a submerged rock just a few miles offshore from Centerville Beach. The ship was carrying 108 persons at the time of the wreck. 70 people were saved, mostly due to the heroic efforts of the local citizens living around Ferndale. 38 others perished. Some bodies were eventually recovered and buried on a bluff overlooking the site of the wreck. Other victims were lost to the Pacific…

In 1921 a white cross monument was built directly above the burial site of the recovered dead. The original monument was destroyed in an earthquake centered in Cape Mendocino in 1991. Local residents rebuilt the monument and it was rededicated on February 11, 1995. It serves as a stark reminder of the dangers of ocean travel – and as a memorial to lives lost at sea in this remote and most beautiful area.

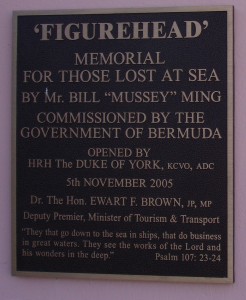

The most enjoyable and satisfying aspect of writing this blog is hearing from strangers commenting on a post or directing my attention to a memorial previously unknown to me. Recently I received an email from Nadia Ming, calling my attention to the Figurehead Memorial on St. David’s Island, Bermuda. My sincere appreciation to her for all the background information for this post. All Photographs in the post are courtesy of Nadia Ming.

The memorial was originally proposed in January 2003, when two fishermen were lost at sea in rough weather. The memorial, by Bermuda artist and native Bill Ming, was dedicated on November 5, 2005 by HRH Prince Andrew, the Duke of York.

I often speculate about the thought process of the artist when writing these posts. This post is special, however, as Nadia Ming provided me with Bill’s original vision for the project.

Maquette for Memorial for Those Lost at Sea

“As an ex-seaman who worked aboard the Queen of Bermuda I felt inspired and motivated to submit my representation of the Memorial for Those Lost at Sea. The theme of maritime life is very close to my art and ideas therefore this sculpture is intended to be a work of commemoration for the known and unknown souls lost to the tides of time yet alive through our memories and chronicles.

This memorial should honour our local fishermen/women who cast their nets and pots to scrape an existence from their catch. Bermudians lost to their loved ones as a result of storms or hurricane and the African slaves who perished during the long arduous Middle Passage.

I have tried to capture these elements, creating the spirit of a beacon that acts as a guiding and welcoming sight in times of storm and calm, a lookout for sailors who sail beyond that horizon of hope.

The form of my sculpture takes the shape of an upturned vessel, which points to the skies and stands erect on a compass due east. Barnacles, shells and a map of Bermuda tattoo the face/mask like limpets clinging to a hulks underbelly. These would stand proud of the surface providing tactile information for people with visual impairments.

Braids of rope frame a cabinet, which houses a paddle for that proverbial creek; an hourglass with sand running out and a life preserver to keep ones head above the water. Overseeing these articles shelters an open logbook that can display the names of all ”Bermudians lost at sea,” alternatively the base could also provide space for names, which would be visually accessible for people in wheelchairs.

I envisage that the final design could be produced in metal (possibly bronze) and/or stone, which would be sympathetic to the site and have durability.”

I believe Mr. Ming captured every element he envisioned in this beautiful memorial. The artist is pictured in the first picture below. I encourage everyone to learn more about Mr. Ming and his art at: http://www.billming.com/index.php

Nadia pointed out two very important additional elements of the memorial in her emails. The first was that The Figurehead Memorial is also part of The African Diaspora Heritage Trail (ADHT), which has been officially designated part of UNESCO Slave Route Project. Take the time to visit the ADHT website at: http://www.adht.bm. I think you will find yourself, like me, spending many fascinating hours learning about “the global narrative of people and culture of African descent” – and the very valuable and important effort to encourage everyone to visit these sites of historical and cultural importance and enrichment.

Information on the UNESCO Slave Route Project can be found at :http://www.unesco.org/new/en/culture/themes/dialogue/the-slave-route.

Men and women of African descent have sailed the oceans since the beginning of recorded history. The earliest known ocean voyages were from Northern Africa to Malta and Crete. During the Great Age of Sail (1600 – 1850) over 20% of all able-bodied seamen were of African descent – some were slaves, but most were free Blacks. Today they still command and crew the warships, merchant vessels, passenger ships and fishing fleets of the world – and daily face the dangers and the majesty of the open ocean.

Approximately 70 names of those lost at sea from Bermuda are engraved at the base of the memorial. All their names can be found at: http://bernews.com/2010/03/lost-at-sea-memorial-full-list-of-names/.

In closing this post, the poem below is inscribed in the open pages of the logbook on the memorial. The poet’s words were inspired by the book of Revelations of St. John the Divine, Chapter 10:5,6 – “And the angel whom I saw standing on the sea and upon the earth lifted up his hand to heaven. And swore by him that liveth for ever and ever, who created heaven and the things that are in it, and the earth and the things that are in it, that time should be no longer.”

THE END OF TIME

“Upon the restless rolling deep

That once the mighty tempest spawned;

Now lies the racing crest asleep.

Beneath that peaceful glassy plain;

All ships and men are there interred;

And all are ‘neath that blanket lain;

Tho’ strove with main now undisturbed.

Beneath that awful silent shroud;

Beneath that fearful mocking stew;

Mingled bone and steel as one

Forever wed as silten brew.

Wreckage, war and nature’s knife;

Trophies piled are theirs to be;

But wills again ‘lasting life,

Victorious, glorious, – NO MORE THE SEA”

By the late Allan E. Doughty Sr. 1922-2013

One of the most satisfying aspects of writing this blog is to hear from people around the world about existing memorials that are new to me and to learn about entirely new memorials nearing completion and dedication. Mike Glaser of the Seward Mariners’ Memorial Committee has been very kind in keeping me advised of the progress of a new memorial in Seward, Alaska that will be dedicated on May 20, 2012. This memorial has taken almost a decade of hard work to bring from concept to dedication – and another 18 months of effort will be required to complete all the aspects of the project design.

It would be difficult to imagine a more beautiful setting for a mariners’ memorial than on this site at the breakwater overlooking Resurrection Bay. The maritime history of Seward began in 1792 and continues through today – whaling, commercial fishing, recreation, and military activities are all woven into the rich fabric of the area. Through the centuries many of those mariners have been lost at sea. The Mariner’s Memorial will become a place where these souls can be remembered and honored. There are also plans to incorporate a section of the memorial in honor of the victims of the 1964 earthquake.

The best way to learn about the memorial is the visit their fine web site at http://www.sewardmarinersmemorial.org/home. Take some time to read about the design and plans for the site, view the construction project photos and videos, and learn more about several of their dedicated volunteers who made this all happen. If you know of someone who should be honored, then please consider ordering a memorial plaque for permanent display. If not, then please make a donation to this fine cause. As I’ve mentioned in this blog before, it’s not always the design and construction funding that is the most difficult to obtain. Ongoing maintenance and care can often be the larger challenge. Please consider donating to this effort.

My home in California is located a few miles from a state park that contains the home and gravesite of the writer Jack London. A museum within the park displays many of London’s original photographs and writings of his time in Alaska. I am quite certain that he once looked out upon the vistas of Resurrection Bay. In addition to writing about Alaska, London wrote one of the enduring classics of maritime life – The Sea Wolf. One of the early lines of this remarkable story concerns burial at sea and its brutal finality…

“I only remember one part of the service,” he said, “and that is ‘And the body shall be cast into the sea’. So cast it in.”

The new Mariners’ Memorial in Seward will certainly be an appropriate place to contemplate the souls lost off her wild and most beautiful shores…

My favorite place in the world is any portion of the shoreline of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia bordering the Bay of Fundy. The rolling hills, trees right down to the waterline, and amazing tides make it an area unlike anywhere else on the planet. It can also be an eerie and strange place at times. Spencer’s Island, Nova Scotia was the birthplace of one of history’s most mysterious maritime events.

My favorite place in the world is any portion of the shoreline of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia bordering the Bay of Fundy. The rolling hills, trees right down to the waterline, and amazing tides make it an area unlike anywhere else on the planet. It can also be an eerie and strange place at times. Spencer’s Island, Nova Scotia was the birthplace of one of history’s most mysterious maritime events.

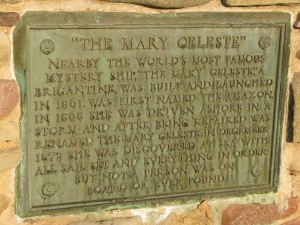

The Mary Celeste was launched as the Amazon from the shipyard in Spencer’s Island in 1861. Following an accidental grounding in Cape Breton in 1868, the ship was repaired and renamed Mary Celeste. On November 7, 1872 she sailed from New York to Italy under the command of Captain Benjamin Biggs. Onboard were Biggs’ wife, small daughter and seven crewmen. The cargo is somewhat in dispute – either wines and liquors, or industrial strength alcohol to be used in paint.

On December 4, 1872 Mary Celeste was found 600 miles off Gibraltar, under full sail, with everything in order except for the fact the ship was abandoned. No sign has ever been found of the ten souls who were once aboard Mary Celeste. She is history’s most famous Ghost Ship.

Many theories have been advanced as to what happened to the crew of the Mary Celeste – from piracy, to a below decks fire caused by alcohol fumes, to a rogue wave or an undersea earthquake. All that is really known, however, is that a ship in pristine shape was found sailing on the ocean without a crew – and that the only thing missing was a chronometer. The cargo was untouched, the ship’s log was found with no mention of any trouble in the last entry on November 24 – everything seemed in perfect order.

The Mary Celeste was salvaged by the captain of the ship that originally found her abandoned. She sailed for many years, eventually scuttled about 1884 on the Rochelois Reef in Haiti. The remains of the Mary Celeste were eventually discovered by the writer and salvage expert Clive Clusser.

In a corner of St. Jacob’s Church (known as the seafarers church) in Lubeck, Germany is a memorial to the windjammer Pamir. The memorial is simple – a salvaged lifeboat from the stricken ship and a board listing the names of the 80 souls who were lost at sea in September 1957 off the Azones.

In a corner of St. Jacob’s Church (known as the seafarers church) in Lubeck, Germany is a memorial to the windjammer Pamir. The memorial is simple – a salvaged lifeboat from the stricken ship and a board listing the names of the 80 souls who were lost at sea in September 1957 off the Azones.

This website is devoted to memorials to those lost at sea, but sometimes it is difficult to ignore the history of some of the proud and beautiful ships that also rest at the bottom of the world’s oceans.

The Pamir was one of the last great windjammers. The four-masted barque was built in Hamburg and launched in July 1905. She was the fifth of ten near sister ships – with a length of 375 feet, a beam of 46 feet, with three main masts that stood 168 feet above her deck. She was capable of deploying over 40,000 square feet of sail area. She carried grain and nitrates to and from Europe, Asia and South America until WWII. In August 1941 she was serving under the flag of Finland.

During WWII she was seized as a war prize by New Zealand, continuing to haul freight during the entire conflict. She made numerous trips from New Zealand to San Francisco, Vancouver and Sydney. In 1948 she was returned to the Erikson Line of Finland, where she resumed hauling Australian grain to Europe. In 1949 she hauled barley from Australia to England, becoming the last windjammer to carry a commercial load around Cape Horn. In the early 1950s she was sold to a German consortium. where she was used as a cargo-carrying school ship on a route primarily between Germany and Argentina.

On August 10, 1957 the Pamir left Buenos Aires for Hamburg with a crew of 86, including 52 merchant marine cadets. On September 21, 1957 she was caught in Hurricane Carrie before shortening sails. She was apparently unaware of the hurricane, being caught with open hatchways. Considerable water entered the ship, the grain cargo shifted and the ship listed severely to port. Her port side eventually went underwater, leading to her loss.

The ship was able to send three distress signals before sinking. A nine-day search for survivors was organized by the United States Coast Guard, but only four crew members and two cadets were ever found. The rest of the crew perished 600 miles west-southwest of the Azores. None of the ship’s officers survived, so there was never any testimony as to how the ship was caught so unprepared for the hurricane.

The memorial in St. Jacob’s Church displays one of the two lifeboats that were eventually found.

Two ships very similar to Pamir can still be seen – the Peking at the South Street Seaport in New York City and the Passat in Travemunde, Germany. Several fine books can also be found that describe the history and final voyage of Pamir:

The Last Time Around Cape Horn by William Stark

The Pamir under the New Zealand Ensign by Jack Churchouse

Tall Ships Down by Daniel Parrott